Kristen Stewart is the most famous actress to play Diana, Princess of Wales. OK, Madonna once wore a tiara for a Saturday Night Live skit, but the best-known Dianas so far have been the distinguished Naomi Watts in Diana (awful) and newcomer Emma Corrin in The Crown (great).

Stewart, 31, is playing Diana in the film Spencer. And Stewart was also in Twilight — the vast tween vampire franchise that made $3.3 billion at the box office and turned its stars, Robert Pattinson and Stewart, who also happened to be dating, into paparazzi gold.

So she has some personal understanding of the fame and pressure Diana felt. Don’t scoff. Between Diana’s death in 1997 and the advent of Twilight in 2008 celebrity changed. Actors were swept into its treacherous waters just as Diana had been before them when, aged 19, her engagement to Prince Charles turned her into a lifelong object of tabloid fascination. And when Stewart was just 18, Twilight plunged her into that world, with the added pressure of the internet and its all-consuming frenzy of obsession.

In Spencer, which tells of a fictionalised Sandringham gathering at Christmas 1991, Diana is at peak fame, about to separate from her husband. When Stewart and I meet in London, I read lines from the film to her that I think may resonate with her own life. “Stand very still and smile a lot,” is one piece of advice aimed at Diana. Another is when Charles talks about public expectations of the royal role: “They don’t want us to be people.”

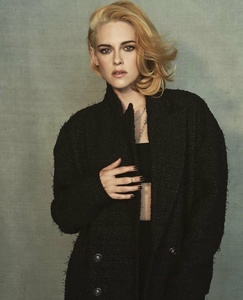

Stewart listens and nods, sipping tea in a posh hotel. She is a slight woman and talks a mile a minute. A-list stars often come across as self-contained, almost regal, but Stewart is skittish and all the better company for it. “Well, I’m not running from anything,” she says, of those Diana comparisons. “The attention is something I can see a parallel in, but the cumulative expectation? Not remotely there.”

“Yet I understand what you’re saying,” she continues. Stewart has a knack of going back to subjects that felt like dead ends, and says she gleaned insights from her own experiences. “It’s feeling constantly watched, no matter what you do. If you’re in public, someone in the room is looking at you at all times. Even if they’re not, it’s at the back of your mind. That is a feeling you only have if you’re extremely famous. It’s a completely different approach to being a human.”

In Spencer, which is more mood than facts, Diana sees an apparition of Henry VIII’s wife Anne Boleyn, who, as a line goes, was “beheaded because they said she was having an affair, but he was the one having an affair”. Again, parallels. In 2012 Stewart was papped kissing the married and much older director Rupert Sanders. The press went wild, and it was tough for Stewart. Two years ago she said of that time: “I feel like the slut-shaming was so absurd.

She stands up, sighs heavily and walks to a shelf of water bottles. The popping of a lid breaks the silence, and she takes a large swig. She doesn’t sit down, but paces in front of her seat. “It is weird to inhabit a space where people are disappointed in your choices. The world is obsessed with celebrities in a way that’s comparable to how we treated the royal family. People want their idols to be a certain thing, because we want to be good people. We think, ‘If they can’t be good, then how the f*** am I meant to be good?’ But I’m not a figurehead.” She pauses. “People choose their role models. But I’m not trying to be one.”

Fame, of course, is what happens to an actress like Stewart, who is in both commercially and critically successful films. On screen she blends the brittleness of Winona Ryder with the sizzle of Jennifer Lawrence. Born in Los Angeles in 1990 to parents in the business, she starred with Jodie Foster in Panic Room at the age of 12. Twilight came half a decade later, but she was not expecting to make a film that would change her life — “If you’d told me we were going to make five Twilights when we did the first? I would not have believed you.” Her ascent to the A-list, then, seems almost accidental.

She still loves making films. How does she pick them? How can she be sure, when she’s read a script, that a film will be any good? “It’s a total crapshoot,” she says. “I’ve probably made five really good films, out of 45 or 50 films? Ones that I go, ‘Wow, that person made a top-to-bottom beautiful piece of work!’ ”

Well, that’s honest. What are the good ones? “I love Assayas’s movies,” she says, meaning Clouds of Sils Maria and Personal Shopper, by the director Olivier Assayas. She won a César for the former, the French version of the Oscars, the first American actress to do so. And the other good films? “I’d have to look at my credit list. But they are few and far between,” she explains. “That doesn’t mean I regret the experience [of making them]. I’ve only regretted saying yes to a couple of films and not because of the result, but because it wasn’t fun. The worst is when you’re in the middle of something and know that not only is it probably going to be a bad movie, but we’re all bracing until the end.”

Would you name them? “No! I’m not a mean person — I’m not going to call people out in public.” But it’s like starting to date someone and going, ‘Woah! I don’t know what we’re doing!’ But when you’re in the middle of a movie you can’t just break up.” She laughs. She really is joyfully candid. Also, she is in a good place now, with a girlfriend, the screenwriter Dylan Meyer, and tipped for her first Oscar nomination as Diana.

I assume that Spencer, directed by the Chilean Pablo Larraín, would be one of her five “really good” films. The Windsors, apart from her two boys, are portrayed ghoulishly. Stewart plays Diana on the edge, prone to late-night wanderings and, at one point, barking at a maid: “Leave me, I want to masturbate!”

Recently Stewart said that female roles used to be “neutered”. I ask her to explain. “We’re just allowed to exist now in a way that feels curious, honest and messy,” she says. “Films have been made for a long time by men and you can tell. We are getting to a place, though, where we can destigmatise things that should not be taboo. We’ve been conditioned our entire lives to go, ‘We’re OK! We don’t feel anything! I don’t have cramps right now!’” (This, of course, said deadpan.) “If men had periods they’d have two weeks off a month. But, anyway, it’s an exciting time to make films, as women can externalise feelings that have been suppressed for ever.”

To play Diana, an actress must master the princess’s eyes, voice and clothes. “I also tried to get taller,” Stewart says. “I’m 5ft 5in. She had such beautiful stature — I thought, ‘I wish I could grow my femur!’ But I’m playing Diana, I’m not her . . . We made a real attempt to make this woman’s light feel unstoppable. She’s at her lowest point, but there’s still this inner fire. Just don’t let it go out.”

Did she consider the impact of the film on those still alive, especially William and Harry? “Obviously, I hope . . .” she says, before trailing off to think. “They have been saddled with the burden of our curiosities for their entire lives and that is the job. [Diana’s] legacy is clearly in her boys. They have obviously made different choices, but they’ve been allowed to make choices, and mistakes. Whereas, before, choices and mistakes were not to be made. Ever. That is a shift. Whether people admire their choices or not, they are making them.”

Is history repeating itself for the Duchess of Sussex, another newcomer ostracised by the Firm? “Not really, because they broke the pattern,” Stewart says, meaning Meghan and Harry have moved to the US for money and to raise chickens. She’s been told Meghan will love Spencer.

We end on how the film starts, with the message on screen: “A fable from a true tragedy.” Fables often convey a moral. What is the moral here? “I don’t think,” she begins, “that the movie is trying to say there was a right and wrong. It speaks to a system that is flawed — it’s very easy to sympathise with every single person.

“All fairytales come to an end. Fairytales are ideals. They’re fake. We make them up to have aspirations and we need those. We need fantasies. But it’s really important to acknowledge individuals within that. To realise that it’s OK to be flawed. And that we can’t leave anybody behind.”

Yes, she’s talking about Diana. But also a little bit about herself.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What do you think of this?