Digital Scans

Click on each image for full view.

You can view each page at the source via each title:

Bold Vision Explores Princess’s Inner World

The door to the roadside fish-and-chips stand opens, and in walks the most famous blonde in the world. Every head looks up and every jaw drops. Smiling, diffident, she approaches the counter: “I’m looking for somewhere. I’ve absolutely no idea where I am. … Where am I?”

Everybody knows Princess Diana, or thinks they do. Certainly, the arc of her life — first splendid, then melancholy and finally tragic — is one of the most familiar narratives of our time.

Yet Diana has always eluded full understanding. The true story of our lives resides inside us, in the moral and psychological paths we follow during our allotted time. Diana’s natural reticence, and the privacy strictly demanded by the family into which she married, have left us with little to go on in terms of reconstructing her interior life. There’s testimony of friends and skeptics, brief glimpses in interviews; not much more.

Until “Spencer,” that is. In an unprecedented work of imagination, acclaimed director Pablo Larraín and screenwriter Steven Knight have forged what they call “a fable based on a true tragedy,” in order to anatomize the private woman behind the public figure. They want us to appreciate her as the Spencer she was, not as the Windsor she struggled but failed to become.

Garnering raves at festivals in Venice and Telluride, their film has taken its place among the best pictures of the year.

Spearheaded by a transformative performance from Kristen Stewart, “Spencer” places us squarely at Diana’s side during three critical days over Christmas in the early ’90s when she made the final break with her marriage and title. But this is no you-are-there docudrama. Rather, it’s an impressionistic collage of sights, sounds and confrontations in which Diana’s in-laws are presented as no less remote and forbidding than the ancestral paintings on the walls of Sandringham, one of the royal family’s private residences located in the countryside of Norfolk, England. And the ghost of Anne Boleyn — an earlier royal wife undone by a husband’s passion for another woman — begins to haunt the princess of Wales’ waking hours.

The film’s earliest moments alert us to expect a mixture of the familiar and the mysterious. A convoy of army trucks rolls along a forest road in the chilly midwinter. Perhaps a Bosnian rescue mission? Close-up on a pheasant in the road, dead on its back beneath the passing wheels. Clearly, no collateral damage will deter this exercise.

Arriving at a manor, pairs of armed soldiers carry heavy green boxes up the ornate steps. Surely they contain ordnance, perhaps to counter a terrorist threat. But no: The boxes are formally opened in the kitchen to reveal enormous quantities of meats, fruits and vegetables, (literally) fit for a queen. Staged by Larraín as a military operation performed with wartime gravity, the spectacle begs the inevitable question: Who in the world could possibly deserve this kind of treatment?

The in-laws offer little solace. “There has to be two of you … the real one and the one they take pictures of,” her husband impatiently spells out. “You have to be able to make your body do things that you hate, for the good of the country.” Her mother-in-law is more succinct: “All you are is currency.” But Diana is not ready to be plastered onto a £10 note. Not yet; not while she has two sons to protect from a similar fate.

In its elegance, and its keen focus on the machinations of power, “Spencer” can stand among many past best picture winners and nominees that take the audience into throne rooms where great decisions are made. Intimate epics like “Elizabeth,” “Nicholas and Alexandra,” “The King’s Speech,” “The Queen” and “The Favourite” are lavishly appointed, even as they critique the politics that support all that luxury. In that vein, Larraín and Knight encourage us to marvel at the corridors and landscaping of Sandringham and its grounds, while offering the most stinging indictment of royal privilege of any major film of this generation. As the future of monarchy is debated in coming years, “Spencer” will likely be found at the forefront of the conversation.

Still, Larraín’s film is fundamentally the story of one who never aspired to royalty, nor took kindly to its demands. So, its real affinities lie with the groundbreaking, award-winning stories of women who endeavor to forge their own identities in the face of male domination and prejudice.

Like the title character in “Mildred Pierce,” Diana labors hard and sacrifices everything in service to her children, not least in the suspenseful outdoor climax of “Spencer” at the Boxing Day shoot. As in “All About Eve,” Diana yearns for a balance between ambition and personal happiness. Her hallucinatory confusion conjures up memories of “Black Swan,” while her heartbreak at the insidiousness of class differences would not be out of place in “Parasite.”

Parallels aside, “Spencer” is truly one of a kind, the product of a gifted auteur and his production team. Among its accomplishments is an original Jonny Greenwood score that pulls equally from Tudor chansons and electronic music, as if to echo the clash of traditional manners and modern mores that animates the story. Young Lady Diana Spencer, yearning for a simple life of caring and giving, found herself thrust into a role she was poignantly unprepared — and unwilling — to play. That is her tragedy, told here with delicacy and power. ✤

Larraín Found New Power by Listening

Having distinguished himself as a fearless artist who thrives in unfamiliar territory, Chilean director Pablo Larraín offers his latest, “Spencer,” an intimate, imaginative account of a formative weekend in the life of Princess Diana.

Dispensing with the historical record to imagine what happens behind closed doors, “Spencer” flips the traditional biopic inside out, restoring fragility and vulnerability to a woman who represented an image of perfection. And, as with his 2016 film “Jackie” about the celebrated first lady, Larraín explores the distance between the visibility of these media-savvy icons and their ultimate unknowability.

“There’s so much that has been said about her, and countless books and movies and TV shows,” Larraín says. “But in my case, the more I research, the less I know about her. There’s an incredible element of mystery. And that is wonderful for cinema. I feel comfortable in that place."

In every new film, Larraín says he usually considers how tone and mood will shape the story he’s trying to tell. With “Spencer,” it was even more crucial, since the undercurrent of emotions shifts and evolves alongside Princess Diana.

“Every decision was made in order to have an emotional connection with the characters,” he says. “And maybe that’s why this is the warmest movie I’ve made.”

Larraín’s definition of warmth defies the traditional: “Spencer” includes unsettling hallucinatory sequences involving the ghost of Anne Boleyn and a dinner made of pearls — surrealist risks he took, offering a rejoinder to the insular, tabloid perspective on Diana.

Producer Paul Webster says, “Quite simply, I think he’s one of the best directors in the world. And I think what was intriguing was this outsider’s view. We have a lot of baggage around Diana in the U.K., and Pablo came to it clean of that and just looked at that story for what it was.”

Larraín was pleasantly surprised when early reviews of “Spencer” called attention to the film’s visual splendor.

“Maybe it’s because once you stop paying attention to certain things, they come out more organically,” Larraín notes.

As a director, he is interested in engaging all the senses, and constantly focused on “movement and perception of speed,” paying careful attention to the ways Kristen Stewart’s Diana navigates her gilded prison. At times, the cinematography generates a sense of claustrophobia, but when Diana roams the countryside in her sports car, “Spencer” is all speed and open space.

Larraín is also attuned to bodily movement. “Spencer” includes a striking dance montage, and Larraín says he filmed the dance with Stewart nearly every day of the shoot for this centerpiece scene. “In the structure of the film, it has a very important role, because there’s so much pressure on the character and then when that part comes in, it decompresses and unleashes what’s coming next in the narrative. But it [also] helped us to understand the movie that we were making and our take on the character — that dance worked as a therapy for us.”

Says Stewart, “Every time [Larraín] started talking about [Diana], she felt like someone he was protecting within his own family. It just felt so considered and so personal. There are a million things that the movie deals with, like invasive media, whether or not the monarchy should be something that we revere. All of that aside, what made me know that he was actually going to do something really truthful was just how intimately he was approaching it. It was like you forgot we were talking about Diana.”

Earlier Larraín period pieces like “Tony Manero,” “Post Mortem” and “No” deal explicitly with the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile; despite his remove from British politics, the director sees “Spencer” as a political drama of a different sort.

“Cinema is always political,” Larraín says. “As soon as you describe a human context, any sort of description of society, it becomes a political idea. Diana went through a huge crisis because she was told what to do. And she was told where to be. And she was told who to be, up until she decided not to be that person anymore. And that’s obviously a political statement.”

Like the evolving tone and mood of the film, Larraín himself is an artist in constant evolution. During the filming of a climactic scene between Stewart and Sally Hawkins, who plays Diana’s royal dresser and best friend, Larraín — so used to exercising his vision in all aspects of filmmaking — realized he had no instruction to give the actors. At first, he was concerned, but upon reflection realized he was exercising a new skill.

“I wish I would’ve learned it earlier, but sometimes directing is understanding when to be quiet. It’s about being sensitive enough to capture things that are happening in front of you, and [recognizing] that you’re not necessarily there to control them. I controlled everything for two years to get to that scene, that moment. Right then, I knew that my job in that scene was to let them connect and bring everything they had to the interaction and just let it happen. And it was wonderful.”

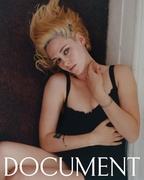

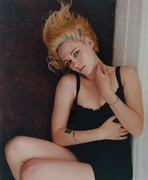

Stewart Took Fearless Plunge Into Her Most Daunting Role

Since the premiere of “Spencer” this September, critics have fallen in love with Kristen Stewart’s portrayal of Princess Diana. The response is an affirmation of Chilean director Pablo Larraín’s absolute conviction that only Stewart was right for the role; a belief so strong he decided not to hold auditions.

“He was so confident and so serious, it was chilling,” recalls Stewart of the first time she spoke with Larraín. “I was like, ‘Who am I to tell you you’re wrong?’ And the way that he described it was exciting. It was genuinely jumping into an unknown.”

Larraín recalls Stewart being “completely fearless” on that introductory call, a conversation that convinced him there was no one else who could portray his Diana. “I needed her as much as she needed to play the character,” says Larraín. “She not only understood the character really well, she also brought something that I think is very hard to see in cinema today — an old-school type of performing: extremely focused, extremely generous, extremely defined and very grounded.”

Where the 31-year-old Angeleno may have lacked a cultural connection to the British royal, her sphinx-like quality in the face of extreme public interest made Stewart the perfect person to embody a figure both loved and scrutinized by millions. Stewart’s ability to disappear into her characters, be they real-life icons or fictitious soul-searchers, only served as further confirmation she would rise to a challenge of this magnitude.

Kristen Stewart found that Princess Diana could be very different depending on the situation, which made her true inner self seem elusive.

Though Stewart’s lack of hesitation in taking Larraín up on his offer may have exuded fearlessness, the closer she got to principal photography, the more daunting the role started to feel. “I was scared, to say the least,” confesses Stewart, who explains how she lived and breathed Diana for months, immersing herself in every bit of material she could find. “There wasn’t a morning that I woke up or [a night that I] went to sleep without thinking, ‘I have to actually do that.’ Theoretically, that’s a very cool idea, but one day it’s going to be the first day. It’s a lot. She’s a lot.”

It wasn’t just nailing Diana’s posture, gestures and diction that posed a challenge: there was the matter of getting to the root of her elusive persona.

“She’s different all the time; the way she speaks to her kids, the way she speaks to a person doing an interview,” says Stewart, adding that, although the film takes place over three days, the intention was always to suggest a greater scope of a life.

Self-confessed to being rehearsal-averse — accustomed to discovering her character’s motivation once the camera starts rolling — Stewart realized she couldn’t achieve this performance without preparation, and spent four months with dialect coach William Conacher building Diana from the outside in. “I’ve never had to do such particular physical work, ever,” says Stewart, who had to let go of her own self-consciousness and let others inside her process. “I had Pablo’s and William’s eyes, as well as my own, on the physical parts of it. I was very open with everyone, like, ‘Honestly, tell me anything. Let’s try everything. I’m open. Let’s figure out our version of Diana together.’ And in between those moments, you have to just live and breathe and forget that you’re trying to be someone else, because this person has to feel alive.”

Stewart’s immersion in the character, from idiosyncrasies to internal struggle, was what sold co-star Timothy Spall on her performance from the moment they set foot on set. “As an actor, there are many ways you can approach a part. One way is doing an impersonation — and it can be an extremely clever impersonation — but there’s another way, which is an embodiment, where it fuses with you and you don’t see the creases,” says Spall. “That’s what I think she does so brilliantly in this: It’s a fusion. It’s a total embodiment.”

It is, however, an approach that comes at a toll. Stewart describes her portrayal of Diana’s mental breakdown as the most loaded, layered, intense, extreme experience she’s ever had, calling the shoot a “three-month mad dash.”

“It was exhausting, lonely, scary and cold. I never stopped running,” she says. “But it’s one of those experiences where the more tired I got, the more encouraged I was. I was so enlivened by the pummeling I was receiving and being able to be like, ‘Yeah, watch this. I’m going to get back up stronger every day.’ The hardest part [about making this film] was the best part of it, because I felt so alive as that character that I just really wanted to fight for her.”

While the film underscores the seclusion of Diana, making the audience feel like they are privy to something secret, that level of intimacy, says Stewart, is a testament to the intense collaboration between Larraín, director of photography Claire Mathon and herself. “Every single day I would be shocked at [Claire’s] intuitive anticipation of what I would do next, because I didn’t even know what I was going to do next. We really did find a synchronicity just because we were so close to each other. We were breathing the same air,” she says. The results speak for themselves: “I felt like the camera was completely inside me, which never happens,” says Stewart. “It’s so rare to work with people just letting you actually be the best you can be.”

For Stewart, the experience was singular and transformative, setting new parameters for the kind of actor she wants to be. “From a personal perspective, [this film] just raised the bar,” she says. “Take the results out of it completely, that is the way that I want to spend my time, just trying to jump higher.”

That the efforts of her labor are being met with critical acclaim comes as no surprise, least of all to those who watched her become Diana. “This is sophisticated character acting at its most seamless,” says Spall. “As she revealed herself, I thought, this is a moment where people are going, ‘Oh, my God, I knew she was good, but I didn’t know she was that good.’” ✤

This is sophisticated character acting at its most seamless. As she revealed herself, I thought, this is a moment where people are going, ‘Oh, my God, I knew she was good, but I didn’t know she was that good.’”— Timothy Spall

DP Mathon Built Trust With Star to Capture Intimate Nuances

On the set of “Spencer,” cinematographer Claire Mathon stood closer to Kristen Stewart than she ever had to an actor on a film set.

It was the only place for the cinematographer to be. Director Pablo Larraín wanted Stewart tightly framed so the audience would feel the same claustrophobia and dread as his version of Princess Diana.

Positioned so close to Stewart at her most vulnerable moments, the French cinematographer also fashioned a kind of safe space to capture Stewart’s enigmatic performance as a doomed princess in a dark fairy tale.

“That was something we managed to find, the two of us, me and Kristen together,” says Mathon. “It was a lot about confidence and establishing trust in each other, but there was also the matter of complicity.”

Mathon followed the actor with short focal length lenses to ramp up the feelings of intimacy on the one hand, and entrapment and fear on the other. She also referenced the frenetic jazz-inspired soundtrack in terms of pacing to mirror Diana’s anxiety.

With the director of photography so close, Stewart had the sensation the camera was recording every nuance of her work, and that this version of Diana would be wholly captured on the 16 mm film the filmmakers chose for the project. For Mathon, this was the entire point. Even though she wanted Stewart and Larraín to feel they could work as freely as possible, she knew the only way to shoot this upside-down fable was to stay with Stewart at all times.

And Stewart loved Mathon’s methods.

“[Mathon] is somebody who opens herself to experience and that’s a remarkable quality for a DP to have,” says Stewart. “There was nothing [Mathon and Larraín] did not see. [The film] was entirely from my character’s perspective.” ✤

Steven Knight set aside traditional biopic structures to write a cinematic snapshot that conjures Lady Diana Spencer as an innocent princess longing to escape from her tower prison.

To screenwriter Steven Knight, an excellent way to jump-start a script is to pose a question to which one doesn’t already know the answer. “Not really knowing where you’re going makes things much more interesting.”

The unanswered question of “Spencer” occurred to him a quarter century ago, during the world’s most famous funeral.

He remembers, “I saw and heard English people doing things that English people don’t normally do, or don’t ever do — which is sob and wail and express grief, openly, in public. And I thought, this is so strange, and even more strange because as I was watching, I was getting emotional! So, I thought, what is going on?”

One possible approach to that question, a conventional womb-to-tomb biopic, was immediately rejected. “You’re not writing it, it’s writing you,” Knight says. “You can’t dwell at any point, you’ve just got to bang out the sequences from beginning to middle to end.”

Instead, Knight opted for a candid snapshot, “like a paparazzi — take a picture over a very limited period of days, in a single location, and just put the pressure on. Put the lid of the pressure cooker on and turn the heat up, and see what happens.” For one particular illustrious family, no get-together was ever hotter than the Christmas holidays during the early 1990s.

“I’m always interested in characters at a moment of decision, which is going to have consequences for their lives,” Knight says, alluding to his award-contending screenplays for “Locke,” “Eastern Promises” and “Dirty Pretty Things.” A wife’s decision to leave her husband, he felt, would allow him to detail stresses and conflicts likely to impel a bird in a gilded cage to fly away.

To shape what director Pablo Larraín would eventually call “the best script I’ve ever had in my hands,” Knight set aside familiar newspaper accounts and biographies in favor of primary sources. “I managed to get access to people who were there, and found out things that actually happened. Always, reality is way more bizarre than anything we could invent.”

There is considerable reality in the film’s settings, to be sure. Sandringham, one of the royal family’s private residences, really is located near the Spencer family home, “and that’s like a gift to a writer,” Knight says grinning. Though the real building has been turned over to charity, on-screen it’s boarded-up and desolate, a potent metaphor for a simpler existence that’s forever lost.

The script’s imaginative speculation on real events admitted fantasy elements, notably the ghostly presence of Anne Boleyn. The screenwriter notes that Boleyn “worked her way into the royal family with an absolute intention. She was anything but innocent … whereas Diana, I think, was innocent. When she entered that household, she had a desire to change things, but also an awareness of the long tradition of fairy tales. And every fairy tale is a horror story as well.”

Certainly, there’s constant menace in the air as Larraín glides up and down the empty corridors. We are never allowed to forget that the monarchy, in Knight’s words, “is as durable as Stonehenge.” Diana “wanted to make it human, and it was probably never going to work.”

Still, classic fantasy narratives always provide emotional release, and “Spencer” is no exception. Larraín and Knight leave us with something as unexpected as it is poignant — a reminder that the complex figure at the center of their story was, more than anything else, a loving mother.

Says Knight, “I want it to feel like a fairy story of the princess locked in the castle, and it’s very scary. But there’s a happy ending.” ✤

Inventive Tonal Shifts Led to Hypnotic Flow

Editor Sebastián Sepúlveda put the audience inside the story.

Editor Sebastián Sepúlveda had to strike a delicate balance with “Spencer” — without calling attention to tonal shifts, he discreetly weaves together elements of psychological terror and a ghostly haunting into the film’s dramatic depiction of a three-day visit Princess Diana (Kristen Stewart) makes to Sandringham, one of the royal family’s country estates.

“I tried to make a hypnotical flow,” says Sepúlveda, who previously collaborated with director Pablo Larraín on his limited series “Lisey’s Story” and the 2016 film “Jackie.”

Editing the film as it was being shot proved to be a successful strategy for capturing exactly what director Pablo Larraín envisioned with his reimagining.

In the opening sequence of cars arriving at Sandringham, Sepúlveda’s cutting was largely dictated by the precise selection of shots filmed by Larraín and cinematographer Claire Mathon. But once inside the claustrophobic royal milieu of the sprawling mansion, Larraín tended to alternate between normal and wide-angle lens shots, leaving Sepúlveda with a stark choice. For a key scene in which Diana and Prince Charles (Jack Farthing) argue bitterly while standing at opposite ends of a snooker table, Sepúlveda decided to only show the two separately, in wide-angle medium shots.

“If I had a change of lens, you might lose the flow,” Sepúlveda explains. “I stay only with those medium shots, because that way you’re inside the tale and you start to feel things.”

Sepúlveda edited the film as it was being shot, giving Larraín a rough cut of the scenes every day. Working together, they completed their first edit of the movie eight days after principal photography wrapped.

“Pablo is not the shy guy who sits at your side during the editing and doesn’t say anything,” says Sepúlveda of their collaboration. “He knows what he wants, and he knows how to get it.” ✤

Greenwood’s Blend Sends Score Soaring

Composer’s unexpected union of baroque and free jazz reinvented monarchal music.

Composer Jonny Greenwood invented a fresh musical approach for Princess Diana in Larraín’s “Spencer.”

Greenwood responded to Larraín with “disparate ideas, some sillier than others.” What they agreed upon — classical chamber ensemble meets free jazz — is surprising.

“The idea,” Greenwood explains, “was to take a traditional baroque orchestra and mutate it by substituting players with free-jazz performers. Films about royalty have a sound, usually a pastiche of classical composers. So, it was about the colorful chaos of Diana against the staid royal family.”

Larraín and Greenwood never met, given pandemic circumstances, but enjoyed a lively exchange: “He sends long voice letters, which is a nice, personable way to communicate,” says Greenwood.

Larraín thought Greenwood’s concept “quite shocking, a very bold idea. I didn’t see how he was able to mix those genres. They’re from different galaxies. He started sending me beautiful Baroque-style music, which created a sense of strangeness and unsettledness.

“Then the jazz came in — played by musicians with controlled improvisation. When there are other characters, Baroque predominates. When it's just Diana — or her with others — we play jazz to suit her mental stress.”

Greenwood assembled a string quartet, jazz band, and the London Contemporary Orchestra’s strings and harpsichord.

He asked the jazz musicians to improvise the classical material, noting, “It’s fun to push into true chaos while the string players are firmly in 1750.”

One of Greenwood’s favorite moments was writing “a piece of formal dinner music that had to unravel ... a really delicious brief to be given, just a few images and the script.” His string quartet dissolves into dissonance, accompanying the horrifying scene of distraught Diana at the royal family’s dinner.

“For a character that needed freedom, [the element of jazz] worked really well,” Larraín says. ✤

Designer Decked the Halls Like Prison Walls

Instead of a backdrop for a happy Christmas celebration, Guy Hendrix Dyas’ surreal sets helped foreshadow the film’s inevitable catastrophes.

What could be more romantic and charming than creating a castle for a film about a princess? Instead of a fairy-tale setting, however, “Spencer” production designer Guy Hendrix Dyas was after something completely different. Something not so sweet.

“We needed [Diana] to feel as though she was a caged bird, or as though she was trapped,” says Dyas. “So, we coined this expression, ‘the elegant prison,’ while we were scouting and this led to a whole new train of thought for us. Rather than trying to replicate Sandringham, the way we wanted to present it was to create a household that on the surface seemed very opulent, very, very beautiful, very inviting, but underneath that thin layer of facade was a very melancholic and sad, depressing reality.”

Dyas made unusual choices to bring the “elegant prison” to life.

The production designer knew director Pablo Larraín viewed the story as a kind of “upside-down fairy tale or fable,” so he was free to move in a surreal direction at times.

“The bed that Diana sleeps in is extremely oversized, like a fairy-tale ‘Princess and the Pea’-style, enormous bed,” says Dyas. “The tapestry that the bed is made up of has medieval-style pheasants painted on them, which, of course, plays into the story later on.

“Diana’s bathroom has that very unusual 1930s caged shower, which is a real thing, but I proposed that to [Larraín] because again it was another one of those wonderful opportunities to exploit Diana as a caged bird. When she looks in, she looks like she’s showering in that caged shower.

“So, all the time we were working to create a level of reality, but also fine-tuning to serve the characters and what they might be feeling like to be in that space.” ✤

Reinterpreting an Icon’s Famed Style

Costume designer Jacqueline Durran and makeup artist Stacey Panepinto avoided directly copying Diana’s look, choosing instead to evoke her ensembles and styles.

When director Pablo Larraín set out to make “Spencer,” he knew Diana was one of the most photographed people ever. He also had ideas about the Princess and his own “Diana.”

The costume, hair and makeup teams on “Spencer” worked with Larraín to bring his vision to fruition.

“I never meant the wedding dress to be an exact copy at all,” says Jacqueline Durran, the film’s costume designer. “I wanted it to be an approximation.”

Durran took a similar approach to Diana’s other fashion statements for the intimate dinners that wouldn’t have been photographed or seen by the public. The stunning clothes were also restrictive, another element Diana hated.

“The clothes had the aura of Diana’s life from 1988 to 1992, but they weren’t exact; we were riffing on what she wore during that time,” says Durran.

Similarly, hair and makeup were more inspiration than precise copy.

“When it came to re-creating her iconic looks in the movie, including the wedding, Kristen and I wanted to find a balance between the real images from those moments and something that was our interpretation,” says Stacey Panepinto, Stewart’s longtime makeup artist. “We never wanted to copy things exactly but just nod to them.”

Panepinto and Wakana Yoshihara, hair and makeup designer for the film, avoided prosthetics and kept Stewart’s appearance natural. With the audience focused solely on Stewart’s acting, she was free to create her version of Diana that fit Larraín’s darkly evocative fairy tale.

Other pieces were used to more directly mirror Diana’s look, though.

“If the hairstyle is done in the right way, the audience will accept that this is the queen or this is Diana,” says Yoshihara. “So I focused on getting the hairstyle right for Diana, especially the one we used with the wedding dress.” ✤

Finding the Miracle Moment

To make their scenes convincingly relaxed and intimate, Kristen Stewart explored her maternal side while the boys playing her sons bonded with her — and with each other.

For the young actors playing Princes William and Harry — 12-year-old Jack Nielen and 10-year-old Freddie Spry — shooting “Spencer” was thrilling. Huge elaborate set; lots of high-tech gear; friendly actors; and welcoming crew. A great adventure.

But Kristen Stewart, who would be their biggest scene partner, admits, “I was intimidated by the kids.”

Growing up as the youngest child, and having been a working actor from an early age, she explains, “I’ve just never functioned around anyone younger than me, ever.”

Director Pablo Larraín, who is a father, encouraged the three to spend time together, anticipating that the former child actor Stewart would bond with the boys following in her footsteps.

His instincts were perfect.

“I liked her straightaway,” says Spry. “She was so fun and we played games. Once we went for a walk in the snow and we were playing and she slipped and got mud literally all over her body. She was so cool about it. We laughed so much.”

Nielen, too, lights up when talking about his time with Stewart: “She is the coolest person I know. She is also super kind, friendly and always very generous with her time, always there to chat and have a laugh. She made everything seem so easy and always treated me seriously — I really liked that.”

Larraín wasn’t just putting the trio at ease. Those hours were a way to guide Stewart to Diana’s determination to be a good mother and protect her children.

“You see pictures of her looking like a lioness protecting those kids,” observes Stewart.

So complete was their bonding that when it came time to shoot the “soldier game,” where Diana, William and Harry share secrets, Larraín turned them loose to improvise. “He just wanted it to be as natural as possible, so told us just to go for it,” says Spry. “Kristen always had jokes or something cool to tell us that totally relaxed my mind and made me feel like I could be Harry in the scene.”

“[Kristen Stewart] is the coolest person I know. She is also super kind, friendly and always very generous with her time, always there to chat and have a laugh. She made everything seem so easy”— Jack Nielen

Nielen concurs: “Everyone was completely wrapped up in the moment — it felt very real.”

When shooting wrapped and the company scattered, Spry says, “although I was so excited to go home and see my family, I was actually really sad. I loved driving around the country lanes singing at the top of my voice in the open-top sports car on the back of a lorry. I don’t think I will forget that ever.” ✤

Digital Scans Gossipgyal