Click on images for full view.

Video Interview

A shorn blonde comes to mind, one whom Stewart will soon portray: Jean Seberg in director Benedict Andrews’s political thriller, Against All Enemies. It chronicles the late actress’s fatal demise brought on by the FBI’s surveillance program COINTELPRO, which targeted and tried to discredit Seberg because of her relationship with Hakim Jamal and the Black Panther Party. “Even though she went through circumstantially, really horrific, tragic things, there was something about [Seberg] that was energetically undeniable,” says Stewart. “She was so misunderstood. It’s not like you need to hero-worship a celebrity, they are just people you want to look at. The fact that people stared at her and fixated on things that were not real, projections: That really ultimately destroyed her.”

Stewart moves like a writer’s actor, speaking in gestural Morse. She signals with her forehead or a messy flip of her hair, conveys apprehension through the stiff energy stored in her shoulders or the round attitude of her chin. Her green eyes are searching—their undertow puffy—her sonic delivery is low-key and annotative.

She rarely appears awkward in motion because her control comes loose. Be it while riding a motorbike in the woods (Twilight: New Moon) or racing a Mustang wearing denim cutoffs (in a Rolling Stones video). She tears toward emotional beats, designing her own architecture of impatience: climbing out of a car before it comes to a full stop (Personal Shopper), exasperatedly listening to a parent (Still Alice), forgetting to unwrap the utensils before wiping her face with the napkin roll (Certain Women), ordering blueberry pancakes (our breakfast).

In November, Stewart opens the reboot of Charlie’s Angels very, very blonde, in a platinum Barbie wig that conceals her asymmetrical crop. Telling the story of a systems-engineer whistle-blower who goes underground and is protected by the Angels, the action comedy is directed by Elizabeth Banks (who also plays Bosley) and costars Naomi Scott and Ella Balinska. Stewart plays Sabina, a Park Avenue heiress turned international spy. She’s a lovable doofus, a show-off with a dopey heart. She has a weakness for chasing bad guys, is prone to close calls and staying chill under pressure. She’s always snacking. It’s a comedic turn for Stewart. “I’m not even like that in real life. [Banks] put punch lines on my jokes every day. I overthink stuff, I make everything way too long. She’s like, ‘Dude, just say it faster.’”

“We wrote her a lot of jokes,” says Banks. “We also improv’d because I come from that background, going all the way back to Wet Hot American Summer—you find something in a moment.” Stewart, says Banks, “lands as many jokes in this movie as any comic actor.” Banks approached writing for Stewart as if it were fan fiction. “What do I want to see Kristen Stewart do in a movie? Like, the fan in me wants to see Kristen Stewart do this. And then I would just make her do it.”

You won’t catch Stewart overacting. She’s like a circuit breaker. Onscreen, if she’s eating a sandwich, she’s eating a sandwich. If she’s trying on a dress, she isn’t posing. She is the image and then the cut. She’s understated and actually cool. The action-packed antics of Charlie’s Angels (horse-racing in Istanbul, gunplay, Krav Maga) intercept the comedy. The movie never slows, celebrating, as is the tradition with this franchise, PG diversion: a dance number turned showdown, spy toys, the color pink, Noah Centineo.

This Charlie’s Angels feels harvested from the same era as the last one—the one from 20 years ago, starring Drew Barrymore, Cameron Diaz, and Lucy Liu. That’s a good thing. It’s extra-lite and pleasantly out of place. The sort of atmosphere that suggests the cast—to put it plainly—enjoyed working together. I ask Stewart why she thinks the tone of Charlie’s Angels is effective despite the movie’s early-aughts pep. Her answer is simple. This is a movie about “women at ease.”

Kristen Jaymes Stewart was born on April 9, 1990, in Los Angeles. She grew up in the San Fernando Valley, to parents she calls “sick,” as in awesome. Their names are John and Jules (“Better than J-e-w-e-l-s,” says Stewart), and they work in film. John is a stage manager and Jules is a script supervisor. Her brother, Cameron, is a grip. She also grew up with an extended family of boys whom she calls brothers. “My parents took in strays,” she says. “My best friend had a really precarious upbringing and became part of the family when he was 13. My brother’s really good friend lived with us all the time. His mom was best friends with my mom. It was like we formed a family. There’s always been an us-and-them vibe, which is really nice and protective.”

She talks about Mickey Moore, her mother’s mentor. He was a godfather figure who worked with Cecil B. DeMille on The Ten Commandments and John Sturges on Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, and did several Elvis Presley musical films. Moore was too old to truly participate in Stewart’s life, but his Hollywood heredity (an entire basement of memorabilia) functions as Stewart’s personal folklore. The making of movies—freed of glitz—runs deep with her.

“I hung out with my parents on set when I was little and asked [them] if I could start auditioning for shit because I saw other kids on set. I didn’t even want to be an actor. I just wanted to be there,” she says. “I was sprinting away from academia. Yet, I’m so intrigued by it. I revere it. I’m almost 30, I feel like a kid. I didn’t go to school. I have a huge chip on my shoulder.”

She reveres a set just as much, though. Over the phone, the director Olivier Assayas—who refers to Stewart as his “soul sister” and who worked with her on Clouds of Sils Maria (2014), for which Stewart received a César award (the first American actress ever), and the supernatural thriller, Personal Shopper (2016)—references her facility on set as a star who hangs out, who sits on an apple box and starts up conversations with the crew.

“It really struck me one day. I had a problem: The film was too long. At some point I said, ‘Why don’t we just simplify the credits. The credits are so full of people. No one ever reads those credits,’” recalls Assayas. “And instantly, Kristen was angry with me. She said, ‘What do you mean? It means the world to those guys. It’s so important for them. For you, it’s a tiny second. For them, it’s vital.’”

When Stewart was 11, she costarred opposite Jodie Foster, playing her daughter in David Fincher’s thriller Panic Room. It’s an intense part that tests the audience’s stamina for suspense. It succeeds because Stewart, like Foster, developed a talent early on for going easy on sensation. Alarm, anger, pure fright: She abbreviates them.

Later, Stewart joined Jesse Eisenberg in Adventureland (whom she worked with again in American Ultra and Café Society), which ultimately lead to her being cast as Bella Swan in Twilight, the vampire-romance franchise that launched Stewart into the stratosphere—and shitstorm—of superstardom. Thanks to a generation of “Twi-hards” who came of age on social media during those five films, who made sport of obsessing over her concurrent relationship with costar Robert Pattinson, Stewart’s private life developed into a tabloid spectacle. That same feverish interest still thrives. In 2017 Stewart hosted Saturday Night Live, and in her opening monologue, while recounting the 11 separate times Donald Trump tweeted about her—all related to her breakup with Pattinson—she goes, “And Donald, if you didn’t like me then, you’re probably not going to like me now, ’cause I’m hosting SNL and I’m, like, sooo gay, dude.”

Inquiring about Stewart’s dating life—she is once again seeing her ex-girlfriend, the New Zealand model Stella Maxwell, who attended the Vanity Fair shoot with her—is futile. Stewart remains smart (and funny) about protecting her privacy. I ask her what she seeks out. She answers, “I only date people who complement me.”

The impact of that confining period in her life is still receding. It was when Stewart started working with independent directors like Kelly Reichardt and Assayas that her work cracked open. “It gave me a chance to not weigh something down. It was so much bigger than me. My baggage was so minuscule in comparison to what [Reichardt’s and Assayas’s] story lines are, as filmmakers. I was finally given a chance to be looked at, not as this thing in this celebrity-obsessed culture that was like, ‘Oh, that’s the girl from Twilight.’”

Does she feel the impact of those misunderstandings, or has she moved on? “I think I’ve grown out of this, but I used to be really frustrated that because I didn’t leap willingly into being at the center of a certain amount of attention, that it seemed like I was an asshole. I am in no way rebellious. I am in no way contrarian. I just want people to like me.”

Next year, Stewart will embark on adapting for the screen Lidia Yuknavitch’s book The Chronology of Water. The memoir, an account of gender, sexuality, violence, and the body, went as viral as a book can go after it was published in 2011, picking up a cultish readership and eventually finding its way into the recommended reading Stewart’s Kindle offered her. With this film, Stewart will be making her feature-length directorial debut, having premiered a short, Come Swim, in 2017. Listening to her speak about first reading the book sounds holy and indoctrinating, as if Stewart mainlined the words. “The way [Yuknavitch] talks about having a body, and the shame of having that. The way that she’s really dirty, embarrassing, weird, gross, a girl. It was a coming-of-age story I haven’t seen yet. I grew up watching fucking American Pie, these dudes jacking off in their socks like it was the most normal thing, and it was hilarious. Imagine a girl coming—it’s like, what, so scary and bizarre. I feel like I started reading her stuff, and she was articulating things that I’m like, ‘Dude, I didn’t have the words for that, but thank you.’”

She wrote Yuknavitch an email. Their connection was fast—they both paint it as fated, like some shared undercurrent. Stewart has since written and edited a draft. She’s read it out loud to Yuknavitch and her husband, who both then cried and held each other while Stewart threw her tattered copy of the book across the room. She was obliterated, relieved.

“It’s harder for me to be an actor as I’m getting older. I’m more comfortable in the idea of making something from top to bottom, rather than giving myself to [it]. There are certain actors who are out of their minds and so transient in their presence that they can actually convince themselves and others of anything,” she says. “I have a harder time doing that as I get older.”

What nearly capsizes Stewart guides her, provokes her to get scrappy. The Chronology of Water accessed what Yuknavitch calls Stewart’s “nomad code.” The actor moved to Portland for a few weeks and wrote, occasionally parking outside of Yuknavitch’s home and sleeping in a Sprinter van with her dog Cole.

She tells me that she allows for stuff or story to occur in time, and for the miracle of instinct to kick in. “Even if there’s one little clam to be plucked in a sea of shit, even if there’s one scene or a line, I need to get closer to that, I need to live that. There’s no equation you can really rely on.”

She tells me about the type of filmmaking that compels her—that might, I imagine, function as her compass when she directs her own film. “I love movies that don’t proclaim to know anything but that literally splatter themselves all over the place, and then somehow, by the end of it, you realize that the only reason they were able to do so was because they were held so preciously by somebody, in that scaffolding. I love Cassavetes. I love all the shit that made us think we can make small movies about things that aren’t plot-driven. But are soul-driven and explorative.” She speaks about movies not romantically, but as the most disclosing format for arranging what’s unfinished.

I’ve never met anyone so synchronously chill and switched on, shaking her leg repeatedly but speaking in rapt chains of thought. She seems deeply clued into the collateral nature of her intuition. She’s hung up on getting things right. Assayas calls her “an actor of the first take.” And Stewart, reflecting on her own writing—the script, her poetry—lights up when she tells me there is nothing more satisfying than finding the exact word to communicate a feeling. “I remember being little and getting crazy anxiety thinking that there were things that you could never express.” That particular tension she attaches herself to—of being open to the unexplained yet hell-bent on “nailing it”—is essential to Stewart’s potency.

“She’s not adapting to anything the industry will want her to do or anything an agent in his right mind would ask her to do. She has been protecting herself, and she has been able to do only what she feels is right,” says Assayas, describing her solo, psychological choreography in Personal Shopper. “I was scared with the places she would go.”

Considering that film’s haunted, more apparitional elements, I ask Stewart: Do you believe in ghosts? “I talk to them,” she responds. “If I’m in a weird, small town, making a movie, and I’m in a strange apartment, I will literally be like, ‘No, please, I cannot deal. Anyone else, but it cannot be me.’ Who knows what ghosts are, but there is an energy that I’m really sensitive to. Not just with ghosts, but with people. People stain rooms all the time.”

Driving her car—a black Porsche Cayenne—Stewart navigates narrow roads and swerving drivers as if she were playing a video game. “Jesus, fuck. Are you seeing this?” I nod. “What the fuck? This is not normal.” She grabs the wheel with both hands: “Move over!” Her flash-fury rises, but just as quick, expires. We talk about Jean Seberg’s French. “Her actual accent is shit, but she says the words perfectly: ‘Tr-ay bee-ehn.’” We talk about L.A.’s vortex-y vibe and how “people are drawn to it and then disappointed by it.” We pass her first girlfriend’s house and as we’re climbing up the street, Stewart shudders.

Stewart is not afraid to crash or explode, as Yuknavitch puts it. “If something blew up in the process, she’d find the most interesting shards that were left, and she’d pick them up and keep going. She is a person who is able to reinvent herself, every single day. I kind of strive for that in my own life. When I met her, I was like, Oh my god, there it is in motion. There it is in a person.”

I know what Yuknavitch is talking about. While hanging out with Stewart at the reservoir, if lulls would waylay our conversation, I almost felt—not that I was disappointing her, but that I had forgotten to add money to the meter. That I had been negligent. A general ineffectualness would settle and I would look around, hoping a dog might soon pass by and visit our bench. “In working with her and talking to her,” says Yuknavitch, “there’ll be these moments of fire and energy, and pulse, and when that’s not happening, well then what’s the point?”

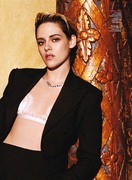

Stewart is burning purpose, presented casually. Even the way she dresses, synthesizing her California roots with a gift for slacker handsomeness, is both determined and unconcerned. Stewart avoids corny suiting; she has mastered the tuxedo without a shirt. She wears shades and cropped T-shirts to LAX, stilettos with Mugler for a Tonight Show appearance, loafers and black latex pants on the red carpet at Cannes. When we meet, she’s wearing blue ripped Levi’s, black Chuck Taylors, a holey HUF T-shirt, and a silver chain-link necklace. Her baseball cap is white; she wears it backward.

All of which illustrates how Stewart has the sartorial potential of someone who could show up to a premiere, ditch her heels, and go barefoot (which she has). As an ambassador for Chanel, her catalog of looks adds an unlikely competence to its luxury. She makes silver lamé look low-pressure and recasts Chanel’s restraint by pairing a pale pink gown with a shaved head. Stewart arrived to this year’s Met Gala in white sequined Chanel trousers, a black top, and orange ombré hair, bringing to mind Katharine Hepburn had she collided in some faraway star system with David Bowie.

“With Chanel, I’ve never been made to feel like I was telling a story that wasn’t being pulled out of me in a really honest way.” Of her relationship with Karl Lagerfeld, who passed away last February, Stewart speaks tenderly. “It’s funny how he presents—so austere and so scary. He wasn’t though,” she says. “He was incredibly inviting—insanely, shockingly unpretentious. He liked what he liked because he liked it. He was a fancy motherfucker, but it was true to him. It’s almost like he sensed he was intimidating, so he was like, ‘No. To have a creative heart is daunting, but let’s get it beating faster and harder.’ He was always touching you while speaking to you. He never talked at you—if he was talking to you, he was usually holding your hand,” she says. “Luckily he knew how to leave a trace. There’s just a feeling that he gave me, an encouraging attaboy thing that shapes you in really profound ways.”

Stewart isn’t a strong swimmer. “I don’t want to enter the water, ever,” she says. “If everyone’s going in the ocean, I’m like, No.” She pulls her hands up to her chest and folds them like paws. “When I’m in the water, I doggy-paddle.” I’d asked Yuknavitch, whose life as a swimmer is fundamental to her memoir and its metaphors, if she and Stewart ever plan to swim together. “We came very close,” Yuknavitch told me. “It’s a little scary for Kristen, but when she talks to me about it, she gets that great look in her eyes. So we sort of have this lingering date with destiny. It’s no big deal, you get in a pool with someone and flap around a little, but because of this feeling I have, that the cosmos sent this creature hurtling toward me that was going to change my life, it seems like a kind of secular baptism.”

There’s something vulnerable and altogether tender about Stewart’s disquieted relationship to the water. She is, in the end, so prototypically California—inclined, one imagines, to catch a wave. And yet, the doggy paddle. It’s the simplest stroke, quiet and plain-delivered. It’s the one we learn first and, strangely, suits Stewart. A clean flutter kick, eyes above the water, and go.

HAIR BY ADIR ABERGEL; MAKEUP BY JILLIAN DEMPSEY; MANICURE BY ASHLIE JOHNSON; TAILOR, TATYANA SARGSYAN; SET DESIGN BY MICHAEL WANENMACHER; PRODUCED ON LOCATION BY WESTY PRODUCTIONS.

Source Digital Scans Gossipgyal

No comments:

Post a Comment

What do you think of this?