When famous actors decide to try their hand at filmmaking, the results can be — and often are — unremarkable by design. Timid and safe with a network TV aesthetic that screams “I’m a lot more afraid behind the camera than I am in front of it.” Not so of Kristen Stewart’s “The Chronology of Water.” Not in the slightest. Some movies are shot. This one was directed.

There isn’t a single millisecond of this movie that doesn’t bristle with the raw energy of an artist who’s found the permission she needed to put her whole being into every frame, messy and shattered as that might be.

“Flowing” is perhaps the word that best describes Chronology of Water, but not in a vacuously metaphorical way. Kristen Stewart has instead managed to translate the flow of words through that of images and sound, to show a filmmaking fluid and strong-willed like a river that becomes more forceful with obstacles in its way. Dynamism and movement is what defines cinema as an art, too, and while this may be a truism, it takes both mastery and discipline to make form fit content so perfectly, on such an elemental level.

Le Bleu du Miroir (in French):

For her directorial debut, selected for Un Certain Regard , Kristen Stewart enters through the front door, with the aplomb of artists who proclaim their convictions and assume their perspective, their voice. With The Chronology of Water , she signs a powerful first film, a visceral representation of female experiences and the power of writing in the long process of healing after the sound and the fury.

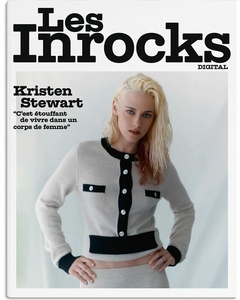

Les InRocks (in French):

Kristen Stewart's directorial debut, "The Chronology of Water," is a crashing wave. Stunningly beautiful and radically powerful.

It grabs you like a wave, puts your head under water, releases it, catches you, etc. It's a great film.

Eight years in the making, Stewart’s truly miraculous “The Chronology of Water” adapts Lidia Yuknavitch’s 2011 memoir of the same name into a ferocious, full-throated cri de cœur without sacrificing so much as a molecule of the source material’s bracing physicality and emotional force. Not taking on the lead role herself but imbuing every frame of this film with the tensile strength we’ve come to admire in her as an actor, Stewart instead directs Imogen Poots to the greatest performance of her career.

The film she has made is simultaneously raw and intricately constructed, as precise and potentially perilous as a Jenga skyscraper. So much visual and aural artifice could easily collapse in on itself, but it holds steady. On so many levels, it is to be admired. Stewart has successfully found a form to match the spiky, visceral quality of Yuknavitch’s prose, as evidenced by readings within the film, and its primary subject: trauma.

Stewart has described her film presented to Cannes as a ‘first draft’ and in that regard it could use some corralling; but equally, like Lidia, it shows fierce potential. As Kesey notes, ‘you can write, girl’.

The boldness and braveness of Stewart as a director and writer are apparent from the start. She decided to film on grainy 16mm and, together with co-writer Andy Mingo (Romance, The Iconographer), she turned the film’s source material, the abuse memoir by Lidia Yuknavitch, into a striking script worth being adapted.

Stewart takes you on a rollercoaster of different tones, emotions and kaleidoscopic colours in the most remarkable way.

Kristen Stewart’s directorial debut is a living, breathing piece of art. It’s a masterful translation of an impossibly difficult life that, while deeply dark, never gives up on the possibility of finding the light.

There’s a beguiling dichotomy in Kristen Stewart’s accomplished first feature as writer-director — between the dreamlike haze and fragmentation of memory and the raw wound of trauma so vivid it will always be with you.

For her feature directorial debut, Kristen Stewart returned to Cannes for the seventh time to show us what she’s made of behind the camera. And show us she did. The Chronology of Water is a boisterous spectacle of the female experience directed with pure love and sincerity.

...there’s no denying Stewart’s sincerity or her clear-eyed commitment to the material. The Chronology of Water may lack the smooth current of a conventional narrative, but it beats with conviction. It’s a bold, promising debut that suggests Stewart is more than willing to dive into the deep end.

If this is the first of many filmmaking endeavors from Stewart, however, we welcome everything that is to come. She’s proven that she’s not afraid to draw blood. And that, in the end, she understands the art of making images flow together in a way that feels just south of transcendent.

Okay, now Kristen Stewart is just showing off.

The Oscar nominated “Spencer” star steps behind the camera, writing and directing “The Chronology of Water,” [...] A portrait of pain, rebirth and reclamation, the film’s heartbeat comes from Stewart’s skillful and natural filmmaking.

Kristen Stewart’s The Chronology of Water rebukes the “vanity project” label often foisted on first time actors-turned-directors with its harsh, disorienting cuts, yielding an immensely uncomfortable movie. Elliptical in structure, but precise in its telling, Stewart’s masterful debut begins with brief, impressionistic flashes of blood from a sudden miscarriage running down the shower drain, alongside the agonizing wails of its protagonist: Yuknavitch, as played by English actress Imogen Poots.

It is a powerhouse performance [Imogen Poots] that roots a film that merits it, and signals Stewart as just as interesting a directorial voice as she is a performer.

The Chronology of Water takes its haunting title from American author Lidia Yuknavitch’s 2011 memoir. And yet, few films feel as deeply personal as this debut by Kristen Stewart, who emerges here as a natural filmmaker.

As a director, Stewart has a keen eye for the immediacy of everyday life. And as The Chronology Of Water reaches its hopeful conclusion, the director produces some of her finest sequences, including one in which Yuknavitch’s father returns to her orbit, proving to be a much different man than in her youth.

Kristen Stewart reveals a deft directorial hand and a distinct, languid, echoing style in her vividly made, emotionally visceral exploration of the life and times of American novelist Lidia Yuknavitch.

But for all that, and some callow indie indulgences, this is an earnest and heartfelt piece of work, and Stewart has guided strong, intelligent performances.

The strongest parts of The Chronology of Water are those character reveals—especially the quieter ones, when a wrung-out Yuknavitch, after a punishing gauntlet of sex, drugs, and alcohol, slowly finds the path to redemption by writing her way out of personal oblivion. That’s when Stewart’s dogged devotion to the source material shines though in a way that signals a major filmmaking talent.

For her feature directorial debut, the actor Kristen Stewart has chosen to adapt a tough, lyrical memoir about a woman trying to out-swim a traumatic childhood and addiction. In The Chronology of Water, the writer Lidia Yuknavitch details the sexual abuse she experienced at the hands of her father and its long aftermath, from a scuttled competitive swimming career to new purpose found, years later, in writing. It’s a difficult piece, but Stewart has shown in her acting work that she’s a fan of daunting tasks.