Click on images for full view.

BTS Video

BTS Video

Kristen Stewart is looking ahead

After being catapulted into global stardom as a teenager in The Twilight Saga, Kristen Stewart moved on to more challenging roles, winning acclaim for her performances in thought-provoking independent films. Now, as she returns to the mainstream with Charlie’s Angels, she opens up about her fluid sexuality, directorial debut and finding the freedom to be herself.

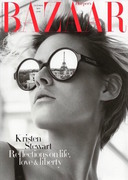

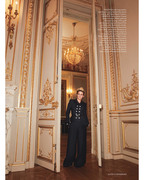

In a vast downstairs ballroom in the Shangri-La Hotel in Paris, I can hear Kristen Stewart before I see her, changing behind a patterned screen in a far corner. Her voice is distinctive – that easy, low-rolling Californian accent, where all the words run together, and she sounds like nothing could surprise her.

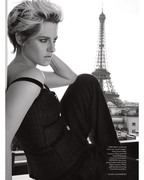

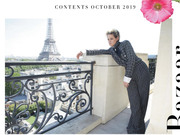

When she finally emerges to go and have her picture taken on a balcony with the Eiffel Tower rising up behind her, she is in perfect contrast to her delicate, gilded surroundings. Her hair is a black-blonde swipe across her forehead, and she’s wearing floor-length black velvet, a black bow at her throat, as befits her status as a Chanel ambassador. She walks past, a bold, swaggering walk, and smiles. "Yeah," she says, seeing my face. "It’s intense. It’s a lot of look."

Soon enough, she’s back, and changed. Ripped jeans, white T-shirt, bare feet: her more natural state. We talk on a warm terrace, cross-legged on sofas. I don’t know why I expected her to be reticent or shy, but probably because that is how she is always assumed to be, or how she comes across in photographs, when her expression sometimes seems deadpan, reluctant to give anything away. Or perhaps it’s just how we all remember her from the Twilight years as the permanently tortured, lovesick Bella Swan. "I try to avoid the word 'awkward'," Stewart says, remembering that time. "I want to reclaim that word, because it’s been used too violently against me."

Today, Stewart is anything but awkward. She is relaxed, open, garrulous and expressive, arms gesticulating as she talks, her voice clear and confident. Take, for example, how she describes meeting Elizabeth Banks for the first time (Banks has directed Charlie’s Angels, which comes out in November, featuring Stewart as one of the leads). The pair happened to be at the same party at the Venice Film Festival a few years ago. Stewart was dancing, but a little self-conscious. "I just didn’t feel as solid as I do now," she says. Banks, by contrast, was having a ball. She came up to Stewart, told her she was a fan and asked if she was having a good time. "And then she said what would be the most annoying thing to hear from anyone else," says Stewart, "which was, 'You’ve got to have fun with it.'" She grins at the memory. "I was like, 'No shit! I’m trying.'"

This is how Stewart talks – frank, candid, plenty of swearing. She seems both sure and totally unafraid of saying what she thinks. It’s as though something has fallen away: caution, certainly, but also a former antipathy towards the whole publicity game that has haunted her on a global scale ever since the extraordinary success of Twilight. "Every day I get older, life gets easier," she says, smiling broadly.

Stewart was only 18 when the first Twilight movie came out. As the child of a script supervisor (her mother) and a stage manager (her father), she’d spent time on sets growing up, and had been acting in films since she was 10 years old (her first was The Safety of Objects, quickly followed by Panic Room with Jodie Foster). But it was the Twilight franchise that made her internationally beloved. She and her co-star and then-boyfriend Robert Pattinson would sit in press conferences with an expression of traumatised horror on their faces. They refused to discuss their relationship, and in interviews there was often a sense of a wall going up, of shutters closing. Most of the time, Stewart looked like she wanted to run away.

"When me and Rob were together, we did not have an example to go by," she recalls. "So much was taken from us that, in trying to control one aspect, we were just like, 'No, we will never talk about it. Never. Because it’s ours.'"

After the final Twilight film was released, Stewart’s departure from the mainstream was pronounced. She acted with Juliette Binoche in Clouds of Sils Maria, a role for which she was the first American actress to win a César award. Her choices were varied and unexpected: she played a psychic in Personal Shopper and made a movie about falling in love in an emotionless society (Equals). Her career became, as she describes it, "the most random game of hopscotch". She chose to work with friends instead of big names and didn’t mind making what she calls "weird, risky mistakes".

But now, in another twist, there’s Charlie’s Angels, her most mainstream movie for years. The internet lost its collective mind when the trailer came out – Kristen Stewart, the ultimate cool girl, doing stunts, doing comedy. "I did Charlie’s [Angels] because I’m a huge fan of Liz Banks and I always felt she vouched for me," she explains. "I always felt, like, she doesn’t think I’m a freak." It was still an act of friendship, but one that allowed Stewart to show off her little-known goof ball side and exceptional fighting skills. When her friends watched the trailer, they told her: 'Dude, that’s you. Finally!'"

If the idea of Stewart as goofball seems unlikely, then be reassured: she can still be intense. Looking back on those early years, and the strange sensation of being an object of fascination in your teens, makes her reflective. There were plenty of aspects of her fame that she found daunting, but what confused her was the sense that her public felt they both knew her and owned her, and then were let down when she wasn’t who they presumed she was.

It was as though she’d become a character, I suggest. "Totally," says Stewart."I’ve tried to say this before, and I don’t think I’ve ever articulated it properly... but people get mad at you because you’re in such a grand position, so if you don’t hold that up, you don’t deserve it. I never valued the fame thing as much as I valued the experiences I got to do while working, and it perplexed me so much... Some people were like, 'You ungrateful asshole!' and I was like, ' Yeah, completely, I don’t want to be famous, I want to do my work!'"

An ode to Kristen Stewart

These days, Stewart has mellowed. She knows there will always be expectations, but she also knows that she doesn’t have to meet them. When she looks around at younger actors and how they handle their position – the Instagram activism, the campaigning zeal, the ability to communicate directly and honestly with their fans – she’s amazed. "They have this insane agency," she says. "And the confidence! That is baffling! I’m like, how are you so confident? You’re so young!" Sometimes, she’s sceptical: the virtue-signalling can be a little forced, a little on point. She names no names, obviously, but describes, tantalisingly, "a couple of people who are like real activists, really at the forefront of progress, and I’m like, 'You are a deplorable fraud! And all you really care about is people looking at you.'" As I said, she’s unafraid.

But she’s grateful, too. It is partly thanks to the next generation, their openness and bravery, that she has found her voice, and no longer seems to care about the consequences of using it. "I used to sit in interviews and go, 'God, I wonder what they’re going to ask me,' but now – literally – you can ask me anything!" So I take her at her word, and enquire what it feels like to constantly discuss her sexuality, now that it seemed to have become a subject for open debate.

"Well," she says, "I think I just wanted to enjoy my life. And that took precedence over protecting my life, because in protecting it, I was ruining it." In what way, I ask. "Like

what, you can’t go outside with who you’re with? You can’t talk about it in an interview? I was informed by an old school mentality, which is – you want to preserve your career and your success and your productivity, and there are people in the world who don’t like you,

and they don’t like that you date girls, and they don’t like that you don’t identify as a quote unquote “lesbian”, but you also don’t identify as a quote unquote “heterosexual”. And people like to know stuff, so what the fuck are you?’

Stewart’s realisation, which she credits the younger generation with giving her the confidence to stick to, was that she was not required to answer that question. She has no answer. She doesn’t identify as bisexual, she doesn’t identify as a lesbian, she doesn’t like labels. She’s a different person every day she wakes up and delighted by that. "I just think we’re all kind of getting to a place where – I don’t know, evolution’s a weird thing – we’re all becoming incredibly ambiguous," she explains. "And it’s this really gorgeous thing."

She accepts that she has become a sort of standard-bearer for that ambiguity. But she doesn’t mind. If she can make the conversation about sexuality easier for anyone, she’s happy. She also couldn’t care less about the impact any of this might have on her career. In the past, she says, "I have fully been told, 'If you just like do yourself a favour, and don’t go out holding your girlfriend’s hand in public, you might get a Marvel movie.'" She looks almost amused at the memory. "I don’t want to work with people like that." Now, by contrast, people approach her, drawn to that undefined sexuality, wanting to make movies about it. Stewart shakes her head in mock despair. "Literally, life is a huge popularity contest."

For the next couple of years – whoever she happens to be dating– Stewart will be busier than ever. Back when she was a kid, on set with her parents, she told her mother she was going to be the youngest person ever to direct a feature film, and that she’d do it before she was 18. "Thankfully I did not do that," she says now. But it’s finally happening next year, as she approaches her 30th birthday. Just 40 pages into reading the memoir, The Chronology of Water, about a young swimmer dealing with addiction, she sent an email to its author Lidia Yuknavitch. "I was like, I will read your book until the day I die." recalls Stewart. She bought the rights, and has spent years writing the script, which she recently read aloud to Yuknavitch. "It was a really, really satisfying feast of an intimidating experience" says Stewart. "I like being intimidated, so that’s fine."

The script isn’t finished – she wants to keep it fluid, open to interpretation. She has a sense of how she wants to do it, but also understands what a responsibility it is, being in charge of a cast and crew. "I know how precious it is –I’ve done it," she says. "I can’t wait to make sure that I don’t mess up anyone’s chance to be great."

She can’t believe her luck: that she gets to spend hours, years, thinking and talking about her favourite book to make it into something new. And this is just the beginning, she hopes: there are half a dozen other projects she’s keen to make. In the meantime, she’s not going to stop acting. If anything, directing is just a natural extension of the process – one that she hopes will make her a better actor. But there’s also an attraction, inevitably, for someone who has been the subject of a collective gaze for so long, in switching positions, going behind the camera. In her new state, feeling free and compulsively honest, perhaps it’s a more natural place to be.

As she puts it, just before she pads back to the ballroom on her bare feet: "The thing that’s really igniting me is the idea of starting the ball rolling – and not being the ball."

After being catapulted into global stardom as a teenager in The Twilight Saga, Kristen Stewart moved on to more challenging roles, winning acclaim for her performances in thought-provoking independent films. Now, as she returns to the mainstream with Charlie’s Angels, she opens up about her fluid sexuality, directorial debut and finding the freedom to be herself.

In a vast downstairs ballroom in the Shangri-La Hotel in Paris, I can hear Kristen Stewart before I see her, changing behind a patterned screen in a far corner. Her voice is distinctive – that easy, low-rolling Californian accent, where all the words run together, and she sounds like nothing could surprise her.

When she finally emerges to go and have her picture taken on a balcony with the Eiffel Tower rising up behind her, she is in perfect contrast to her delicate, gilded surroundings. Her hair is a black-blonde swipe across her forehead, and she’s wearing floor-length black velvet, a black bow at her throat, as befits her status as a Chanel ambassador. She walks past, a bold, swaggering walk, and smiles. "Yeah," she says, seeing my face. "It’s intense. It’s a lot of look."

Soon enough, she’s back, and changed. Ripped jeans, white T-shirt, bare feet: her more natural state. We talk on a warm terrace, cross-legged on sofas. I don’t know why I expected her to be reticent or shy, but probably because that is how she is always assumed to be, or how she comes across in photographs, when her expression sometimes seems deadpan, reluctant to give anything away. Or perhaps it’s just how we all remember her from the Twilight years as the permanently tortured, lovesick Bella Swan. "I try to avoid the word 'awkward'," Stewart says, remembering that time. "I want to reclaim that word, because it’s been used too violently against me."

Today, Stewart is anything but awkward. She is relaxed, open, garrulous and expressive, arms gesticulating as she talks, her voice clear and confident. Take, for example, how she describes meeting Elizabeth Banks for the first time (Banks has directed Charlie’s Angels, which comes out in November, featuring Stewart as one of the leads). The pair happened to be at the same party at the Venice Film Festival a few years ago. Stewart was dancing, but a little self-conscious. "I just didn’t feel as solid as I do now," she says. Banks, by contrast, was having a ball. She came up to Stewart, told her she was a fan and asked if she was having a good time. "And then she said what would be the most annoying thing to hear from anyone else," says Stewart, "which was, 'You’ve got to have fun with it.'" She grins at the memory. "I was like, 'No shit! I’m trying.'"

This is how Stewart talks – frank, candid, plenty of swearing. She seems both sure and totally unafraid of saying what she thinks. It’s as though something has fallen away: caution, certainly, but also a former antipathy towards the whole publicity game that has haunted her on a global scale ever since the extraordinary success of Twilight. "Every day I get older, life gets easier," she says, smiling broadly.

Stewart was only 18 when the first Twilight movie came out. As the child of a script supervisor (her mother) and a stage manager (her father), she’d spent time on sets growing up, and had been acting in films since she was 10 years old (her first was The Safety of Objects, quickly followed by Panic Room with Jodie Foster). But it was the Twilight franchise that made her internationally beloved. She and her co-star and then-boyfriend Robert Pattinson would sit in press conferences with an expression of traumatised horror on their faces. They refused to discuss their relationship, and in interviews there was often a sense of a wall going up, of shutters closing. Most of the time, Stewart looked like she wanted to run away.

"When me and Rob were together, we did not have an example to go by," she recalls. "So much was taken from us that, in trying to control one aspect, we were just like, 'No, we will never talk about it. Never. Because it’s ours.'"

After the final Twilight film was released, Stewart’s departure from the mainstream was pronounced. She acted with Juliette Binoche in Clouds of Sils Maria, a role for which she was the first American actress to win a César award. Her choices were varied and unexpected: she played a psychic in Personal Shopper and made a movie about falling in love in an emotionless society (Equals). Her career became, as she describes it, "the most random game of hopscotch". She chose to work with friends instead of big names and didn’t mind making what she calls "weird, risky mistakes".

But now, in another twist, there’s Charlie’s Angels, her most mainstream movie for years. The internet lost its collective mind when the trailer came out – Kristen Stewart, the ultimate cool girl, doing stunts, doing comedy. "I did Charlie’s [Angels] because I’m a huge fan of Liz Banks and I always felt she vouched for me," she explains. "I always felt, like, she doesn’t think I’m a freak." It was still an act of friendship, but one that allowed Stewart to show off her little-known goof ball side and exceptional fighting skills. When her friends watched the trailer, they told her: 'Dude, that’s you. Finally!'"

If the idea of Stewart as goofball seems unlikely, then be reassured: she can still be intense. Looking back on those early years, and the strange sensation of being an object of fascination in your teens, makes her reflective. There were plenty of aspects of her fame that she found daunting, but what confused her was the sense that her public felt they both knew her and owned her, and then were let down when she wasn’t who they presumed she was.

It was as though she’d become a character, I suggest. "Totally," says Stewart."I’ve tried to say this before, and I don’t think I’ve ever articulated it properly... but people get mad at you because you’re in such a grand position, so if you don’t hold that up, you don’t deserve it. I never valued the fame thing as much as I valued the experiences I got to do while working, and it perplexed me so much... Some people were like, 'You ungrateful asshole!' and I was like, ' Yeah, completely, I don’t want to be famous, I want to do my work!'"

An ode to Kristen Stewart

These days, Stewart has mellowed. She knows there will always be expectations, but she also knows that she doesn’t have to meet them. When she looks around at younger actors and how they handle their position – the Instagram activism, the campaigning zeal, the ability to communicate directly and honestly with their fans – she’s amazed. "They have this insane agency," she says. "And the confidence! That is baffling! I’m like, how are you so confident? You’re so young!" Sometimes, she’s sceptical: the virtue-signalling can be a little forced, a little on point. She names no names, obviously, but describes, tantalisingly, "a couple of people who are like real activists, really at the forefront of progress, and I’m like, 'You are a deplorable fraud! And all you really care about is people looking at you.'" As I said, she’s unafraid.

But she’s grateful, too. It is partly thanks to the next generation, their openness and bravery, that she has found her voice, and no longer seems to care about the consequences of using it. "I used to sit in interviews and go, 'God, I wonder what they’re going to ask me,' but now – literally – you can ask me anything!" So I take her at her word, and enquire what it feels like to constantly discuss her sexuality, now that it seemed to have become a subject for open debate.

"Well," she says, "I think I just wanted to enjoy my life. And that took precedence over protecting my life, because in protecting it, I was ruining it." In what way, I ask. "Like

what, you can’t go outside with who you’re with? You can’t talk about it in an interview? I was informed by an old school mentality, which is – you want to preserve your career and your success and your productivity, and there are people in the world who don’t like you,

and they don’t like that you date girls, and they don’t like that you don’t identify as a quote unquote “lesbian”, but you also don’t identify as a quote unquote “heterosexual”. And people like to know stuff, so what the fuck are you?’

Stewart’s realisation, which she credits the younger generation with giving her the confidence to stick to, was that she was not required to answer that question. She has no answer. She doesn’t identify as bisexual, she doesn’t identify as a lesbian, she doesn’t like labels. She’s a different person every day she wakes up and delighted by that. "I just think we’re all kind of getting to a place where – I don’t know, evolution’s a weird thing – we’re all becoming incredibly ambiguous," she explains. "And it’s this really gorgeous thing."

She accepts that she has become a sort of standard-bearer for that ambiguity. But she doesn’t mind. If she can make the conversation about sexuality easier for anyone, she’s happy. She also couldn’t care less about the impact any of this might have on her career. In the past, she says, "I have fully been told, 'If you just like do yourself a favour, and don’t go out holding your girlfriend’s hand in public, you might get a Marvel movie.'" She looks almost amused at the memory. "I don’t want to work with people like that." Now, by contrast, people approach her, drawn to that undefined sexuality, wanting to make movies about it. Stewart shakes her head in mock despair. "Literally, life is a huge popularity contest."

For the next couple of years – whoever she happens to be dating– Stewart will be busier than ever. Back when she was a kid, on set with her parents, she told her mother she was going to be the youngest person ever to direct a feature film, and that she’d do it before she was 18. "Thankfully I did not do that," she says now. But it’s finally happening next year, as she approaches her 30th birthday. Just 40 pages into reading the memoir, The Chronology of Water, about a young swimmer dealing with addiction, she sent an email to its author Lidia Yuknavitch. "I was like, I will read your book until the day I die." recalls Stewart. She bought the rights, and has spent years writing the script, which she recently read aloud to Yuknavitch. "It was a really, really satisfying feast of an intimidating experience" says Stewart. "I like being intimidated, so that’s fine."

The script isn’t finished – she wants to keep it fluid, open to interpretation. She has a sense of how she wants to do it, but also understands what a responsibility it is, being in charge of a cast and crew. "I know how precious it is –I’ve done it," she says. "I can’t wait to make sure that I don’t mess up anyone’s chance to be great."

She can’t believe her luck: that she gets to spend hours, years, thinking and talking about her favourite book to make it into something new. And this is just the beginning, she hopes: there are half a dozen other projects she’s keen to make. In the meantime, she’s not going to stop acting. If anything, directing is just a natural extension of the process – one that she hopes will make her a better actor. But there’s also an attraction, inevitably, for someone who has been the subject of a collective gaze for so long, in switching positions, going behind the camera. In her new state, feeling free and compulsively honest, perhaps it’s a more natural place to be.

As she puts it, just before she pads back to the ballroom on her bare feet: "The thing that’s really igniting me is the idea of starting the ball rolling – and not being the ball."

Interview by Sophie Elmhirst

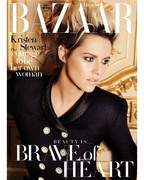

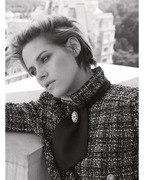

Kristen Stewart wears Chanel Haute Couture top and Chanel sunglasses.

Styled by Miranda Almond

Photographed by Alexi Lubomirski

Hair by Adir Abergel

Make up by illian Dempsey

Manicure by Christina Conrad

No comments:

Post a Comment

What do you think of this?