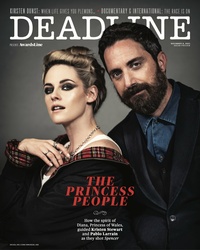

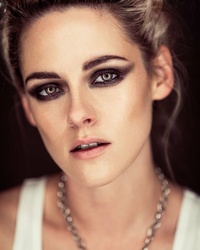

After a charged premiere at the Venice Film Festival, Pablo Larraín’s Spencer has become one of this season’s hottest contenders. A haunting study of one particular Christmas at Sandringham for Diana, Princess of Wales, as her marriage falters and the Royal fairytale turns grim, Spencer features a landmark performance by Kristen Stewart that has catapulted her to the top of the Best Actress race. Joe Utichi meets Larraín and Stewart to dig deep into the production.

What was the jumping-off point for Pablo Larraín and Kristen Stewart for the film that would become Spencer? The pair share a look and laugh.

“It’s a very reasonable question,” Larraín says.

“And a reasonable start of a conversation,” Stewart agrees.

'Spencer' Director Pablo Larraín And Writer Steven Knight Mixed Fact With Fable To Explore An Unknowable Princess Diana - Contenders New York

But it’s also impossible for them to know how to respond. “Depending on how we answer the conversation can go any which way, so which conversation is this going to be?”

The truth, of course, is there were a million jumping-off points. “We could articulate different versions and they’d all be true,” Larraín says. There are the tangibles: the fascination with Diana that both shared, the script by Steven Knight that focused a narrative on a three-day period marking a crucial turning point in Diana’s relationship with the Royal Family, the sheer challenge of bringing to life a figure that had meant so much to so many people.

Larraín, for example, saw his own mother in the story, and found some a point of connection with another English-language movie of his, Jackie, which had told a similarly confined narrative of an iconic woman, in the immediate aftermath of JFK’s assassination. For Stewart, Diana was a “cool” figure whose death had an impact on her, though she had only been 7 years old at the time. She was also obsessed with Netflix series The Crown, and fascinated by the inner workings of the unknowable Royal Family.

But there were other reasons to do Spencer that, to this day, neither party can fully explain. A kind of energy that drew them to the film’s set—a grand palace in Germany standing in for the Sandringham estate. There was an energy on set they never wanted to let go of, and the story they were telling felt like a moment of victory for Diana as she made the decision to leave “The Firm” behind… even though they never lost sight of what would happen to her next.

What drew them to the film, then? “There’s something in the simplicity of this that is probably the most deep,” says Larraín. “It’s just: there’s a movie in her.”

“There’s nothing more,” Stewart adds. “That’s the whole thing.”

DEADLINE: There’s an aspect to this movie where it feels like it formed as you were making it. You obviously had a solid script and a structure in place, but the movie feels very organic, even ethereal. Did it feel that way on set?

KRISTEN STEWART: The script is very precisely written, and in a way, it has a very composed feeling, but the way it has been captured feels very much like you’ve just caught something that’s falling off a table before it shatters apart.

You would maybe think, as well, with a movie that tackles a subject matter as coveted and well-covered as this one, that there would be more rehearsal. We talked about the script a lot, and I learned my lines word-for-word. I never lived in the accent, but I spent so much time making it a physical, involuntary thing that when we got there, there were embedded intentions and little buried treasures everywhere.

How we found these things was: everything felt fleeting. It felt very much like we didn’t have a ton of time to shoot the movie, and so we didn’t map anything out or rehearse. Or even block… there wasn’t a shot list. Every day was walking into that space, knowing those scenes by heart and going, “Gosh, I wonder how these are going to come out. I wonder how they’ll unspool.”

And it always felt as though we had a unison that allowed us to be really messy, but always I felt that we caught it at the last moment. I never felt unseen. I never felt something that I was feeling deeply, internally wasn’t somehow being physical in the room. It was somehow materializing in the room in this weird way that we were all able to catch. Because sometimes you have those feelings and you’re not speaking the same language. The visual vocabulary is not in unison with the performance. You think, I’m doing stuff and it’s not translating.

In this case, to do so little actual blocking and planning and then have it present itself… it’s the most fun way to work, but it’s also scary to do because if it’s not the right combination of people, what happens is you go, “Oh, man, we’re not doing anything.”

PABLO LARRAÍN: It absolutely was the right people. Everyone that we admire so much. People like Jacqueline Durran on costumes, Guy Hendrix Dyas on production design, Jonny Greenwood with the music, Claire Mathon the DP, and all the incredible English actors.

But I was thinking on that word you used: ethereal. This movie is set in a world that is very unusual for everyone. The Royal Family is not reality anyway, but also this is a period movie. If we were making a movie set this far back in the ’80s, the movie would be set in the ’50s. 30 years, it’s a lot.

So, you combine the distance of time with a natural disconnection with these people who are so isolated in their own traditions and history and logic. Getting in there and feeling empathetic is very hard. And it’s not needed, I think… right up until the point where Kristen lets you in. That’s where it flips. If it didn’t happen, there would always be glass between the audience and the movie, and the movie would be very different. It would be colder.

It could be interesting…

STEWART: I was just going to say, the more you describe it, I’m like, “I’m in!” [Laughs].

LARRAÍN: It could be. There’s an idea of art that you observe the object and you’re never reflected in it, and that creates a distance that’s very interesting and moves you in a different way. But there are other types of art, and cinematic exercises, where the dance of empathy becomes very interesting, and it depends on who you are that would determine that.

I’ve been listening to some of the interviews that our heads of department have done, and it’s incredible how they all approached Diana in a different way. Everyone has a different opinion. Claire is French, Guy is English. So is Steve Knight, and he said that in a world so hard and harsh today, having the chance to focus on someone like Diana was a relief. All of a sudden, you go back and understand that a person that was so relevant and famed for so many reasons is ultimately someone so human. We need her here, now. It would be incredible to have her around. People can relate to her in their regular lives.

STEWART: She was a born leader in that sense. Those are the people that you really aspire to be, and not even in a way that’s literal, but in a way that makes you feel closer to being human. You look at her and go, “I like my species.” She’s wonderful, she’s an encouraging force. It’s such a powerful thing and it’s so rare, but those people rise to the top for a reason.

DEADLINE: In your research, did you conclude that she wanted to be a leader like that? There must have been love between her and Charles to begin with, but do you think she wanted that opportunity to speak to people like that?

STEWART: From a very young age she said that she knew that was what she was going to do; that she was going to be very important. She tied that to the idea that she would marry someone really important, and this was way before Charles was a literal aspect of her life. It’s in all the interviews, and everyone who knew her as a kid was like, “It’s so crazy, but she said that.” She always said she was going to be destined for something bigger.

LARRAÍN: When I read that for the first time, I felt it implied a sense of real tragedy.

STEWART: Right, because there was this weird isolationist mentality even before she found herself; before her plight was that loneliness itself. She always was separating herself from the crowd a little bit. There were certain things she didn’t do, certain things she avoided. She was like a social butterfly, but also not at all. She was saving herself, quite literally. She knew in some weird, psychic, strange way that there was something to preserve if she wanted ultimately to become that person.

I think she knew she wanted to marry someone who was very important so that she could be, by osmosis, close to that power. And especially during that time, that’s what those girls are taught. That’s one way for women to be important. From this perspective, and this modern scope, that sounds crazy, but it’s the way it was.

Did she want to be with Charles? I think she believed in the fairytale. She spoke about the bubble being burst, and the fall from that being violent because the belief in it was real and true. To have those fantasies and that disillusionment at such a young age, and then the subsequent pressure of having to perpetuate something that is not only not true but painful, is so much for someone who is only just developing the skills of being a human being on this planet. She’s barely in her 20s and she has a baby. It’s just so much. I remember being that age, and I can’t imagine having that stunted experience, and to then be judged so harshly for the way she functions in the world. What chance did she possibly have?

Actually, she did such a great job. It didn’t even take her that long to revive the love that was completely taken from her, even though she gave it up willingly. But sure, willingly did it on whose terms? On terms that were farcical and not real.

DEADLINE: Perhaps that’s what’s so relatable, too. Inherent in the human condition is the notion that satisfaction is illusive because there are always going to be caveats to our dreams.

LARRAÍN: I think something that’s striking to me about that is her last words after the car accident. Someone comes to her aid, and she looks at that person and asks, “What happened?”

STEWART: And it’s not literal. There’s something about those words where it sounds referential to her whole life.

LARRAÍN: It’s not, “What happened in the last 10 minutes?” It’s “What happened?” It’s a bigger question. And that is the most moving, absurdly painful destiny.

STEWART: Oh god. Even now… it was something that occurred to me so often while we were making the movie, and those fucking words were ringing in my head all the time. To ask that of someone you don’t even know.

In this weird world in which she exists as a character in my mind, I imagine her speaking her last words to someone she doesn’t know and who doesn’t know her and didn’t realize who she was at the time she said that. He didn’t immediately know it was Diana, he was just wrapped up in dealing with this horrific accident. For her to reach out to a stranger, because there was no one close to her…

DEADLINE: The movies are obviously telling very different stories, but the moment of Diana’s death was a seismic event for the world, as JFK’s assassination had been. Pablo, did you see any point of connection there between Jackie and Spencer?

LARRAÍN: Not in that sense, because I think that the Royal Family is a very English mythology, whereas Diana is universally personal. It’s not the same, and I think the reason why people care about the Royal Family is because they’re fascinated by the melodrama. That’s all it is, particularly outside of the UK. In the case of Diana, people see the reflection of themselves on her.

I think that Spencer and Jackie are very different movies. Maybe because we shot that assassination so graphically—in that movie, we wanted to do it graphically. Everyone who had shot the assassination of JFK before had done it from afar, and we put the camera right in the car because we wanted to see the impact it had on her. But with Spencer, we went in the other direction. It’s way less graphic because we’re not even in that moment [of her death]. We’re away from that tragedy. We’re in another moment, and it’s a moment where she’s deciding to walk away from that house, from that family.

STEWART: It’s a moment of victory.

DEADLINE: Spencer is so internalized. We follow Diana’s perspective so closely that the people around her exist on the margins. She must decide to let them in, and she rarely does. And yet as an audience we need to feel let in by her, to feel reflected in her. When you’re making a movie like this, how essential is it to trust in your own instinct for how to toe that line?

STEWART: I think it’s really essential to personalize it, because what you said is key: everyone feels reflected, so therefore your reflection is valid. And it’s the only one worth examining, because you can’t do everybody’s at the same time. There’s no way to play the perfect historical figure of Diana. Or anybody, but especially her, because of what you just said. Then, like Pablo said, all the department heads came at her and found ways to her that were varied, and I think that collaboration is key and it’s totally essential that people feel free to express and have a director that will hear them.

When a movie is unique and feels in and of itself its own thing, whether it’s good or bad—fuck good or bad, it’s its own beast—it’s because it is always funneled through this one person. A good director is able to take everyone’s selfishness and be even more selfish. To funnel it through his own lens. If you’re able to feel like a movie is completely yours and you’re not even the director, that’s remarkable. That’s the right feeling, but it’s a self-delusion because the movie actually is that director’s. It’s the best feeling because when you feel like that, you’re able to own it. And I feel like this movie is mine.

LARRAÍN: I think what you’re saying is very important and it’s very beautiful, but I would add that I personally enjoyed every moment of making this movie with you.

STEWART: Me too.

LARRAÍN: Usually, when you finish, you’re exhausted. As I told you when we finished, I would have kept filming it. We ended up in London, and it wasn’t very pleasant because we had so much press and it became another thing.

STEWART: Well, it was interesting because we were now the ones that were being hunted.

LARRAÍN: Yeah, of course, but when we were in those very controlled spaces in Germany, in this big house, we would walk in, and it felt like everyone was having the most incredible time.

STEWART: Oh man, the weird thing was how much fun this was to me. It’s like a weird high. There was an absolute intoxication happening. There was a slap-happy, super exuberant, fluttery feeling. Even when we were doing scenes that were exceptionally sad and heavy.

Pablo described the movie like a meteor that we were passing back and forth, and it was burning. There’s a hysterical nature to that. But also, as we’ve been saying, Diana was such a wonderful person that we felt her light refracted all over our set. And even if it was just our imaginations coming to life, through our imaginations she connected us to each other, and it felt like taking drugs. It felt so cool, so good.

It’s so fun to be strong and powerful and funny and sexy.

LARRAÍN: It can’t get better than that. It’s very beautiful what you said and it’s true; it made everyone put joy into it. The work can be heavy, and it can be exhausting, but the material was just so fascinating. The places, the people.

I remember when we talked on the phone for the first time, Kristen, I was like, “You know this will be a long ride. We’ll be together a long time, and I hope it works out.” And you were like, “Yeah, yeah, I know…”

STEWART: Yeah, because you don’t know [laughs].

LARRAÍN: You don’t know. But it was an incredible time. Of course, at the beginning it’s scary, because of the subject and the human materials in the story. But cinema is made beat-by-beat, right? It’s a slow process that involves hundreds of people running around, but in the end, it’s just a camera on very few actors, and it’s a moment of silence. It all builds up to something very specific happening in a brief moment in time. “Let’s be present right here, right now.”

I was scared before we started shooting because of this wheel of desire that could take you anywhere, but once we started, I enjoyed it so much and I felt that everyone was having a really beautiful time.

STEWART: It’s so rare to not have it become a slog at some point. That feeling where you’re like, “Fuck, OK guys, I can tell everyone’s tired and it’s day 28, but there are 37 days…” Where we still have a lot left, but we’ve done a lot already, you know? I genuinely never felt like that.

There was a certain point where I got a bit tired of walking around the grounds, because the only way to give that montage shot scope was to shoot little bits of it every day, but it was also the most beautiful meditative therapy session of a scene that carried us through the whole thing.

There was never a point where it felt like we were slacking or that we had to encourage the crew. There’s always usually a point where the actor brings in an ice cream truck [laughs]. There’s always like, “Fuck! We need to get a coffee truck!” I mean, I can’t remember if we did anything like that, but we didn’t really need to. We really were all skipping.

DEADLINE: That moment of silence you described, Pablo, after a team of hundreds of people have set up a shot, when you call action. Describe what that moment feels like for you.

LARRAÍN: It’s the only way to do it. Especially in the era of masks, everyone is walking around with their faces covered, and all I’d have to communicate with is my eyes. We would just look at each other and we’d know when we got that moment. It would be, “We’re moving!” Or, “Check the gate!” Because we shot the movie on film, so we fucking had to wait for the gate to be good.

STEWART: Oh god [laughs].

LARRAÍN: And sometimes there was hair on the gate or something and we had to try and get it again.

STEWART: That was fucked. I mean, that’s one of the beauties of shooting on film—especially 16mm film, which is a trickier hair-in-the-gate situation. But it’s a young actor’s mistake to think there’s not a new way into a moment that most of the time, if you’ve done it once, coming back to it you can go deeper. There were a lot of moments like that on this movie.

And you and I got so good at communicating with the masks on, even from very far away. There were times where I’d be like, “Boom, we’re done,” and then we had to do it again, sometimes a couple more times because the first one back was shit. It sometimes threw me that we would ever have to re-examine a moment that had lived so completely. But that’s what’s cool also.

LARRAÍN: It’s a crazy thing because you know that take with the hair is still usable, right? It makes it more expensive because you must clean it.

STEWART: Yeah, and when he told me that, it was not at the beginning of the shoot. It was kind of towards the end [laughs]. I was like, “Ohhh…”

LARRAÍN: But at the same time—and look, I don’t want to get into this mystical shit, but I do believe in certain things that cinema creates, and [shooting on] film creates. There’s a rhythm. You have to load it and unload it and it’s not cheap. All the actors know it when you start filming. You have to be quiet, be precise. It’s not like digital where it’s like, “Oh, you’re rolling? I didn’t even know.” It just creates a different, good tension, so if there was a hair in the gate, OK, let’s go again.

I worked years of my life to try to make movies like they were complete accidents, even with no script. And this was an exercise in controlling everything right up to the point that we were actually making it. It’s a different approach and I loved it, and what comes out of it is an exercise that is all the more sophisticated because of how you got there.

STEWART: I’ve never prepped a movie like this in my life, and I’ve also never felt freer or more unbound. It might have been counterintuitive for me as a younger actor, but actually, oddly, it’s the way to really act. It’s the fucking way to fly through something.

We chipped away at it. It felt like one little foot in front of the other every single day. I like shooting out of order, especially in a movie like this where it wasn’t like I had to contend with a huge age gap. In this sense, I enjoyed days where there would be a scene from the beginning of the movie and a scene from towards the end, because it made everything feel very close.

LARRAÍN: And possible. Because it takes so much weight out of you. If you’re doing the whole movie scene by scene, you only see what’s still to come. By shooting out of order, it’s just this little moment. Just this idea. Just focus on the little thing, and then the next one, and then the next one.

STEWART: Who knows how different the movie would have wound up if we had shuffled a different deck of cards in the schedule. Had we just had a different reason to do it like we did. You learn certain things and then you take those things into the next day, and you build upon the scene that might come before or after. You don’t know how, if you shuffle the deck differently, it would have been informed.

DEADLINE: Were there ever moments of wanting to go back to something you’d done earlier because of what you’d later learned?

STEWART: Not really. To be completely honest, maybe a couple moments, but my immediate reaction to you asking is no. Perhaps there were one or two things where I would have been overthinking because I really wanted them to land and be good, but there was nothing I was ever like, “Hey, do you think that we could go back?” Because if we had needed to do that, we were usually in a position where we could have gone back and done it.

LARRAÍN: It is so amazing when you work so hard around something and then it actually happens and it’s so short. That moment of capture is so short and fleeting.

STEWART: I know. Sometimes we would get it and you were like, “Should we do it again? We might as well, because we’re here.” But oftentimes it would be the first or second take that probably wound up in the movie, and it became, “Let’s just taste it one more time because after that, that’s it. This is the last meal.”

LARRAÍN: The thing is, this is just like music. Sometimes you hear a song you like, and you imagine that person maybe only played it once. You can spend years of your life listening to that song, and it took them three minutes to record it. It’s incredible.

STEWART: Yeah, it doesn’t matter if it was played a million times since, because that recording was just once. I always have visual flashes of them writing the song or recording it. I imagine myself there.

LARRAÍN: I just saw the trailer for Peter Jackson’s Beatles doc, and they were preparing the song “I’ve Got a Feeling”. That song will last forever, and how they created it is fucking cosmic. It’s incredible how time is just this weird perception. Sometimes on set you feel like you’re flirting with things you don’t fully understand, but the capture of that is short, and it’s nice that it’s short. I don’t like to do 50 takes. At most, maybe, we did 12, but the regular amount was three or four.

STEWART: There’s a cycle where the first few takes work and feel truthful, and then something falls out, but you keep going and you push through that to try and get back to it. It’s torturous and punishing as a process, though it can be fruitful on some occasions. But it doesn’t feel good, it feels bad. When you struggle to do anything, I don’t know if something really feels worth it. It’s not that it should be easy necessarily, but it should feel natural.

LARRAÍN: I’m not talking about you, but I’ve worked with actors where they wait, where they don’t get there on the first take. They do it slowly and they expect seven or eight takes, so they treat the first four or five takes as a rehearsal. Here, nobody worked like that. And with Kristen leading the charge…

STEWART: I do the opposite. I start at 11 and take it down from there.

LARRAÍN: So, when we’re working with actors who are not with us all the time, they come and they see that, and they honor it, so it only needs a few takes. It creates a good kind of tension in everyone, from the actors to the focus puller and everybody.

STEWART: That’s what I was going to say. I’ve been doing this a very long time, so it would be falsely modest not to acknowledge that focus and pacing can be controlled. The absurdity of pretending to be other people is inherently embarrassing, and it makes other people embarrassed not only because it’s odd, but because it’s really vulnerable and, at least at first, it’s fucking ridiculous. The only way to push through that, and not build awkwardness, is you take it as high as you possibly can, and maybe that’s too much but on the next take you can bring it down.

It’s very nerve-racking to have a small amount of time on screen in a movie like this that is so intense. You only have a few opportunities to find your character, so it’s hard. It’s really hard. It’s so nice to be able to say to those actors, “We’re not working up to this. We’re ripping off the Band-Air right now.” People are exhilarated and surprised and shocked out of being too embarrassed to be vulnerable or whatever the fuck. It’s really the best part. You gotta lead with confidence, even if it’s false at the start. You have to fucking stick your head in.

DEADLINE: Does that extend to your drive to create? Not to be bleak about it, but do you, in some sense, feel the ticking clock of the finite time you’re on the planet?

STEWART: It’s funny, I was just thinking about something similar to this general subject two days ago because I had this immediate existential fear. I had a feeling of impending doom that if it ever did stop, it actually would be scary. I have friends and a dog, and I have a life that feels personal and normal and provincial, in the sense that my whole life isn’t just working. But pretty much, I go from one thing to the next, and I always have a ton of things going on, or I’m always trying to find the thing. If that did stop, it would be scary.

So, I had that thought of like, If I lost my greatest interest, would I have no reason to be? It becomes: what is life for? These are just things you sip coffee and think about sometimes. Not all the time, but the other day I said, “Fuck, thank god I have one or two things to keep me occupied because I can’t be contemplating infinity all the time.” It’s super addictive. It’s just a way to be here, you know what I mean? [Laughs].

LARRAÍN: I don’t think, in my case, you never really know what you’re doing. It’s a strange thing to talk about a film, because I personally must come to an understanding of what I want to say about the movie. It becomes a process, but there’s something in the desire of the filmmaking itself to meet you at that unknown place with materials that can be fascinating and dangerous at the same time. There’s something that pulls you in, that lets you exist, which is so simple. “How come it could be so fascinating to see Diana?” It’s so simple.

I remember on the first day, Kristen walked in, and I had my camera and it was: “This is it!”

STEWART: It did feel crazy [laughs]. It was so fucked up and freezing cold, but before that moment—before we actually went to make the movie—I felt like I was just playing dress-up, because we weren’t doing the scenes.

There was a moment where Pablo told me to go back and start from where I began again. He said, “Just relax, and slow down, and hold the whole movie. Walk in, and hold the whole movie.” And that wasn’t a scene, but it was a scene.

Everybody has asked me what was the first moment I felt the character, or felt like I had gotten her, but that was the first moment where we were doing the thing and it was the three of us moving together—me, Pablo and Claire—where I could tell as soon as we cut. I saw Claire pull away from behind the viewfinder and it’s always the same look of: something just happened. It was like we all saw the same ghost.

LARRAÍN: You know what also happened that day? I remember exactly the moment you’re talking about, where you walked over to the window, but it was also the first time we were quiet again, right? And I heard the heels…

STEWART: Yes! On the wood floor. So haunting.

LARRAÍN: There, I understood something that was so important for this film, which is the heels. It’s about the heels. She’s trapped to the heels, so the connection she has with that space is through her feet. And you wore them even in close-ups, right, Kristen? Maybe sometimes when you were dancing you wore sneakers because it was not possible.

STEWART: I was scared [laughs]. I was genuinely afraid I was going to fall down. I even told them, “If I fall, do not fucking cut. Don’t have anyone run in, because men on set—which I appreciate, especially certain bigger dudes like stunt coordinators or grips or the camera operators—they are literally supposed to take care of you and would very naturally rush and go, “Are you OK?” I’m like, “Literally, if I break my face on the marble floor and you don’t fucking shoot that… I swear!” [Laughs].

-----

You can download this Deadline digital issue here.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What do you think of this?