Olivier Assayas didn’t read the screenplay for Kristen Stewart’s directorial debut, but he would have greenlit the project immediately.

“This is the movie of someone who needs badly to make a movie,” he tells Stewart over Zoom one morning in November. Assayas, who directed the 35-year-old actor-turned-filmmaker in 2014’s Clouds of Sils Maria and 2016’s Personal Shopper, knows a thing or two about a film made on one’s own terms at all costs. For Disorder, his own 1986 feature debut, he was offered the crew of the monumental French director Alain Resnais. Assayas turned the opportunity down, opting to continue working with his far less seasoned peers. “The foundational decision I made in filmmaking,” he continues, “was not to go the safe route.”

With The Chronology of Water, an adaptation of championship swimmer Lidia Yuknavitch’s memoir of the same name, Stewart demonstrates the safe route is of no interest to her either. The Imogen Poots-led deep dive into the long shelf life of trauma refuses linear narrative or easy viewing. The reviews it received out of Cannes, where it premiered in May, testify to Stewart’s ability to successfully helm an unconventional project. American audiences will see for themselves when the film arrives in theaters Dec. 5, but Stewart has already proved her mettle to the audience member she cares about most—herself. The Chronology of Water spent almost a decade in development limbo, a period during which the actor became well acquainted with rejection. “Every producer in town was like, ‘So what’s it about? A swimmer who gets raped by her father?’” she tells Assayas. “That’s just a hard no.”

It’s telling that it was a little-known indie distributor, the Forge, that picked up the American rights for the film, reaffirming for Stewart that Hollywood is no petri dish for independent cinema these days. “You have to leave this country to do that,” she insists.

But Stewart isn’t done with the industry just yet. Next year, she’ll star in her wife Dylan Meyer’s directorial debut, The Wrong Girls, opposite Alia Shawkat. The film will be her first comedy, proof that even someone who has been a fixture onscreen since the age of 9 can still surprise us. She’ll follow that performance with her first TV series, The Challenger, where she plays a member of NASA’s first diversified class of astronauts in 1978. Also in the queue is Full Phil, where Stewart acts as Woody Harrelson’s estranged daughter on a Paris trip gone awry.

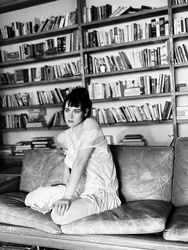

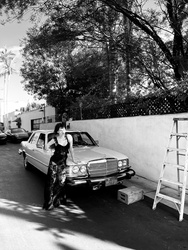

For this Artists on Artists issue cover story with Assayas, she sifts through the victories, obstacles, and lessons of a life spent on the screen.

Olivier Assayas: I can see the notes for your film on the wall behind you. Do you function like that?

Kristen Stewart: Well, I’ve only functioned once in my life, this being my first [directorial] project. It was necessary to see the movie as a body, because some of the fractured memories in the story needed to find a different circuitry.

Assayas: You are disturbing the logic of how a film has to be made because you have an intuitive knowledge of what it is, of what it should be. This film is adapted from a book you love, which is an excellent starting point. At the same time, it’s a self-portrait. I think it’s very close to the bone.

Stewart: I just wanted to be the person who got the ball rolling. I’m a really good follower. I’m such a faithful soldier, but it’s really fun to lead the charge. I thought this book really lent itself to adaptation because it lacks any kind of structure that makes it easy to digest or palatable. I was like, This feels so much more like a whole life, a DMT trip, or a dreamy recollection. This is a film about one person—but that doesn’t mean it was easy to make. We draw ourselves every single day. Sometimes that self-portrait’s hideous, disgusting, self-hating, lacerating. Other times, it’s cool. To attempt to say something true about yourself or a character is such a slippy, squirrely thing. Making movies is inherently embarrassing because it’s egotistical.

Assayas: I see it as a privilege. It’s about understanding the world in ways that are not open to everybody. You have to be constantly aware of that, and you must be up to the task.

Stewart: Which is why women don’t normally do it—we are not trained to accept that. It’s not our first instinct to fill that role. It’s audacious. That’s what the book’s about, too—her finding her voice. If it feels like a self-portrait it’s because, look, I’m 35 years old. I’ve wanted to make movies since I was 9. Why the fuck did it take me so long?

Assayas: Ultimately, it was an epic. It was a fight. It was a war. And you won the war.

Stewart: It’s just a way of relating to reality. It’s not fundable entertainment industry fare. The script was very hard to read. I guess now that I’ve done it—not to sound too dramatic or self-aggrandizing, but against all odds—there is the feeling that execution is inevitable. I’m not gonna sit around and wait for someone to pay for my movies ever again. I’ll just do them for fucking nothing. I will steal them. I will not wait another eight years to make a movie. I will just operate in Europe in complete liberated isolation, and then hope that some American distributor will buy it after we make it. Independent cinema in America is a farce. People are going to fucking quote that all over the Internet, but it’s true. I apparently make independent movies, and it’s like, barely.

Assayas: I wrote to you after watching the film. I was just so happy for you because I felt that you had the fight of your life and you won. It reminded me of how I started making movies. My first screenplay was not as abstract as the movie you made, but it was daring for the times. I remember a producer who told me, “You know what? I’m producing a film by Alain Resnais, the famous French filmmaker, and I’ll give you the crew. You will have an experienced crew that will guide you.” I wanted to make that movie with the guys I’d been working with when I made my short films, who were my age, who shared my taste. The foundational decision I made as a filmmaker was not to go with the seasoned professionals, but to trust the kids I’d started with. Sometimes, a film crew can be like a punk band.

Stewart: I’ve seen you talk about that first movie, and it genuinely encouraged me to avoid “studio musician” engineers that have been suggested to me. The times when the movie found itself about to fall apart were when people who were overly experienced were sinking the ship, and they needed to be removed. Our producers were not confident, thrilled, or happy with me at all.

Assayas: When you want to break the mold, when you want to make movies that open doors for yourself and for other people, it’s going to be tough. No one understands where you’re heading—not because you are so far ahead, but because you are somewhere else. What do you think art can do?

Stewart: It can make the world a much bigger or smaller place. We make art to get closer to each other, but at the same time, when you make really good art, the vacuous spaces that you find yourself inhabiting as an actual human become immense. What can art do? I don’t know. Keep a lot of people from offing themselves?

Assayas: I think art is a disease. You’re born with it, you know? I need to have my back to the wall to be able to make anything, because it comes from insecurities. When you’re acting, writing, or directing—there is pain. You deal with the pain, and art is the result. You also have to protect it—from the industry, from the boredom of modern droning. Movies are living proof that at least there’s one kind of art that can reach the mainstream. I started as a painter, a clumsy painter, but a painter. I dropped the idea of being a painter because I knew I would never connect with my times, whereas the power of movies is the fact that you can communicate with more people. Art is about proving that it can be done.

You can purchase a copy of the Artists on Artists issue, featuring this conversation and many more, here.

Makeup by Jillian Dempsey

Hair by Bobby Eliot

Project Management by Chloe Kerins

Photography Assistance by Dan Patrick

On-Set Styling Assistance by Kat Cook

Styling Assistance by Andrii Panasiuk

No comments:

Post a Comment

What do you think of this?