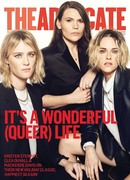

Holiday and movie magic converge on a below-freezing February evening in a Pittsburgh suburb. Film crew members bustle on the grounds of the Fox Chapel Golf Club, where earlier that day, they’d made snow to emulate a white Christmas. Meanwhile, in a moment of pure serendipity, Mother Nature lays down a few inches of the actual wintry stuff.

Inside the venue’s storied clubhouse, extras playing party guests mingle in fine holiday threads. The hall is decked with twinkling lights, and the decorations are punctuated by a magnificent Christmas tree. It’s day 18 of a 29-day shoot for Clea DuVall’s second feature film as a writer-director, Happiest Season, the first-ever studio-backed holiday rom-com that’s centered around a queer love story. Although it’s late in the day and the cast and crew have been at it for hours, the room buzzes with energy.

Happiest Season stars Kristen Stewart and Mackenzie Davis as a couple who hit a rough patch in their relationship when Davis’s Christmas-loving Harper insists on taking Stewart’s Abby home to her parents for the holidays. The hitch? While Harper is adventurous and free in her Pittsburgh life with Abby, she’s not out to her overachieving WASP parents, Ted (Victor Garber) and Tipper (Mary Steenburgen). Initially, she introduces Abby as her straight roommate, and that’s where the trouble begins. For anyone who’s ever come out, the notion of going back in is pretty much a deal-breaker. But the women are in love, and the radical beauty of Happiest Season is that it’s a rom-com. Unlike with so many queer-themed love stories that came before it that ended in tragedy, the audience knows going in to DuVall’s film that a happy ending is around the corner.

In the party scene shot at the country club, Harper looks on at her dad, who’s running for mayor of their town. He delivers a speech about family values. Abby stands beside Harper, their fingers grazing and intertwining as they hide their relationship in plain sight. It’s a marvel to witness the energy between the women knowing that Happiest Season will soon join the canon of romantic holiday comedies that have always been the purview of heterosexual love stories. Everything from classics like Christmas in Connecticut and Holiday Inn to the more contemporary Love Actually comes to mind. In recent years, networks and streaming services, including Netflix and Freeform, and now even Lifetime and Hallmark, have tapped into making queer holiday flicks. But Happiest Season, from Sony’s TriStar Pictures, occupies its own space. With theaters primarily shuttered, the streaming site Hulu acquired the film from Sony in late October, where it will premiere.

On set, Stewart and Davis laugh between takes as DuVall, in a knit beanie, a puffy jacket, and a headset, emerges from the crowd of actors, extras, and crew packing the space. A trailblazer for queer women since she starred in But I’m a Cheerleader 20 years ago, DuVall, who speaks openly about her coming-out journey, is the perfect person to make a breakthrough mainstream holiday movie that focuses on a same-sex couple. Not only does it star Stewart, an out A-lister, and Davis, beloved by the LGBTQ+ community since she played queer in Black Mirror’s “San Junipero” episode, Happiest Season costars three more out actors. Schitt’s Creek’s Dan Levy plays Abby’s best friend, John; Parks and Recreation’s Aubrey Plaza is Harper’s ex Riley; and veteran actor Garber is Harper’s dad. Rounding out Harper’s family are GLOW’s Alison Brie as the uptight eldest sister, Sloane, who has secrets of her own, and DuVall’s writing partner Mary Holland, who cowrote Happiest Season and is a natural scene-stealer as Harper’s open-hearted sister, Jane, the middle sibling and the oddball in a family where keeping up appearances is everything.

“All I ever wanted was a holiday movie that represented my experience so I decided to make one,” DuVall tweeted in September when the first still photos from Happiest Season were released.

One of the photos she shared is of Abby and Harper ice-skating while Abby clings to a Rudolph trainer to help keep her upright. The holiday iconography is everywhere in the movie where the love between the women is palpable. Another photo is of Harper’s family on Christmas morning in front of the tree with their pajamas, bathrobes, and bed head. Harper stands behind Abby, her arms around her. There’s no mystery to the eventual outcome of the movie. Everything is going to be OK. And that’s what makes Happiest Season, with all of its holiday cheer, so wonderfully subversive.

“It’s not just a movie that LGBTQ people are going to relate to and connect with. It really is a story that I think has empathy for all of its characters,” DuVall says. “When someone comes out, it’s not even necessarily just about the person’s coming-out. It’s like a tree; its branches splinter off and it becomes a part of other people’s journey too. Which is definitely not a perspective I had until I was much older.

“But it’s also just anybody who has a family, anybody who’s ever gone home for the holidays, anybody who’s gone home with someone else for the holidays. It’s the human experience of going home with someone or going home to be with your family at any time.”

Between camera setups on that winter night, before everything went into lockdown, Stewart and Davis discuss the movie. Stewart, who moved on from the Twilight series to become a star of art-house films like Personal Shopper and Certain Women, came out publicly several years ago. Although she’s from a younger generation of LGBTQ+ people than DuVall, and certainly from her costar Garber (whose first film was 1973’s Godspell), Stewart lauds DuVall’s boldness in making a digestible, fun, and funny movie with a happy queer love story at its core.

“You enter the movie immediately comforted by [knowing it’s a rom-com]. For me, especially, as somebody who would completely identify with a story of this kind, [the audience] is just put at ease in a way that’s immediate,” says Stewart, adding that she was surprised in the best way that it was a studio film. “It’s like, in this beautiful way, indulgent. And it just feels fucking good.”

Davis echoes Stewart’s praise of how Happiest Season handles a same-sex love story.

“It also doesn’t make it an event, which is so nice. It’s two people in love and there is this obstacle that they have to get over. Obviously, that is contingent on their sexuality, but everything else feels ancillary to the fact that they’re lesbians,” Davis says. “There are stories about gay and lesbian couples or a person of some marginalized identity that are tragedies or, at the very least, high dramas. It’s so nice to be like, ‘There will be problems, but they will end up fine.’”

Principal photography on Happiest Season took less than a month, but on set, Stewart and Davis have an easy rapport as they occasionally chime in with a word the other is searching for. DuVall confirms her stars’ undeniable chemistry was there from the start.

While Stewart has carved a path in niche films of late, Davis has starred in sci-fi heavy-hitters Blade Runner 2049 and Terminator: Dark Fate. But she’s truly acclaimed for her queer role in “San Junipero” and as Cam, the intense computer programmer in the criminally underrated AMC series Halt and Catch Fire. The women turned out to be the perfect couple for DuVall.

“It’s one of those things. You can’t plan for it; you can’t rehearse it into being. It’s either there or it’s not, and I just feel very fortunate that these two got along,” DuVall says. “I was very nervous. And they didn’t meet before. I remember the first night they met each other, we all went out to dinner and I felt like I was going on a blind date that I had set up where the people had to get married, and I knew that.”

In turn, Stewart was thankful to have DuVall in helping to make Abby a three-dimensional queer character, which is not a common feat in a mainstream movie.

“I wanted the person I was playing to be incredibly specific. If you’re going to get a dose of this type of person in a commercial movie where you wouldn’t normally get to see them be the protagonist, I didn’t want it to be remotely one-note. I wanted it to seem like this is a person who is fully realized and well acquainted with herself — for those details to come together in a way that you just believed fully,” Stewart says.

“It took her years to find that perfect balance of identity and how to present that in a way that doesn’t make her remotely uncomfortable, or anyone else necessarily, because there’s no confusion there. There is real self-assured shit going on with Abby,” she says. “That is not an easy thing to explain to a straight director or a costume designer. Very few words were required to convey things that would’ve needed to be explained in a complex way to someone who was not of that experience.”

As LGBTQ+ representation increases in film and TV, questions about who should play those roles have come up more and more. The landscape is vastly altered even from when Davis played queer on Black Mirror four years ago.

“We’re living in a time where those questions should be asked about everything we do,” Davis says. “I’m excited to part of any of these conversations and to be invited. I asked Clea when she asked me to do the part if it felt complicated that I hadn’t had this experience. ... You need to know when you’re taking up space that should go to somebody else and when you’re participating in something that you’ve been invited into and have a role to play within that space.

“I like telling really beautiful love stories about queer women, or just female relationships that can address all the complexity of those relationships, but you’re not mourning someone at the end or mourning this horrible life or this punishing existence. These are the sort of things I think effect change — to put positive, normalized genre depictions of relationships that don’t get portrayed that often into the world.”

To watch Abby and Harper’s breezy relationship unfold at the start of the film, to witness their backslide and then their ultimate commitment to love set against the backdrop of all that signals Christmas — ribbons, wreaths, shiny paper, gingerbread cookies, and a soundtrack laden with jingle bells — is sure to be a surprisingly emotional experience for queer people who grew up never seeing themselves on screen. It’s a huge part of the reason DuVall — whose long career has included queer roles in But I’m a Cheerleader, American Horror Story: Asylum, Veep, and in the first feature she wrote and directed, The Intervention — wanted to make the film.

DuVall reiterates that Happiest Season isn’t a political film per se. “That’s not a part of the landscape,” she says.

Still, there’s no denying that the film has the capacity to alter the cultural conversation or, at the very least, to give viewers a conversation starter that also lightens the mood and makes them laugh. Both she and Stewart reflect on how a film like Happiest Season could have influenced them growing up.

“It’s a real chicken or the egg because you don’t really know,” DuVall says. “We all, throughout our lives, pick up this baggage, and sometimes you don’t even know where it came from.”

DuVall speaks to an experience so many young lesbians and bisexual women who never saw themselves reflected can understand.

“It just would have kind of given me a sense of You’re OK, instead of watching Some Kind of Wonderful [the John Hughes-penned movie] and thinking, I want that girl to end up with me, not with him.”

Stewart, who’s been in the public eye since she was a child, recognizes that a lack of visibility in pop culture and media affected her coming into herself and that she was impacted by stigma.

“I was really comfortably functioning conventionally. Only in retrospect [do I] see that if I had just had my eyes opened to more ambiguity in a way that wasn’t weird, I probably would’ve had more crushes on girls when I was little. I just genuinely didn’t.

“I know now that [I was affected by] the world opening up for me a little bit more as I got older. The more artists that I met, people that I met, friends that I had, and different examples of things and ways to love and know each other presented themselves, I was like, ‘I can do that.’

“I didn’t want to be called a lesbo. And I didn’t want to be that weird, gross, ‘dykey’ girl. And that sucks. It’s terrible. But I was always really attracted to, sort of, weirdness and otherness. I would’ve loved to have had more examples of that not being ridiculed and a point of scrutiny. Yeah, that would’ve been awesome,” Stewart says.

The pandemic has denied LGBTQ+ people the opportunity to see themselves in a big-screen holiday rom-com. But sleigh bells ring for Happiest Season November 25 on Hulu. “It’s been a brutal year,” acknowledges DuVall, who hopes her movie will bring much-needed joy to those who need a reprieve from difficult news. But she’s also aware that art and entertainment can change the culture. And who knows, Happiest Season may well do that for the next generation, much like DuVall’s body of work has done for other queer folks.

“I had the great privilege of being a part of But I’m a Cheerleader 20 years ago. At that time, I was definitely not out. Through the years, seeing the impact that movie had on people and how much it helped them…it did what movies are supposed to do, which is make us feel seen and make us connect with the human experience on a deeper level,” DuVall says.

“That really informed what I wanted to do once I got into telling my own stories.”

Photographed by Art Streiber

Kristen Stewart: hair by Adir Abergel, makeup by Jillian Dempsey, styled by Tara Swennen. Stewart is wearing RTA jacket and shorts, ELLIATT white button-up, stylist’s own socks, Thom Browne shoes

No comments:

Post a Comment

What do you think of this?